Multi-Cloud Strategy: Avoiding Vendor Lock-in Without Over-Engineering

Build pragmatic multi-cloud infrastructure that delivers 20% cost savings and negotiating leverage without drowning in abstraction complexity. A battle-tested framework from managing $2.4M annual infrastructure across AWS, GCP, and Azure.

Tech Stack:

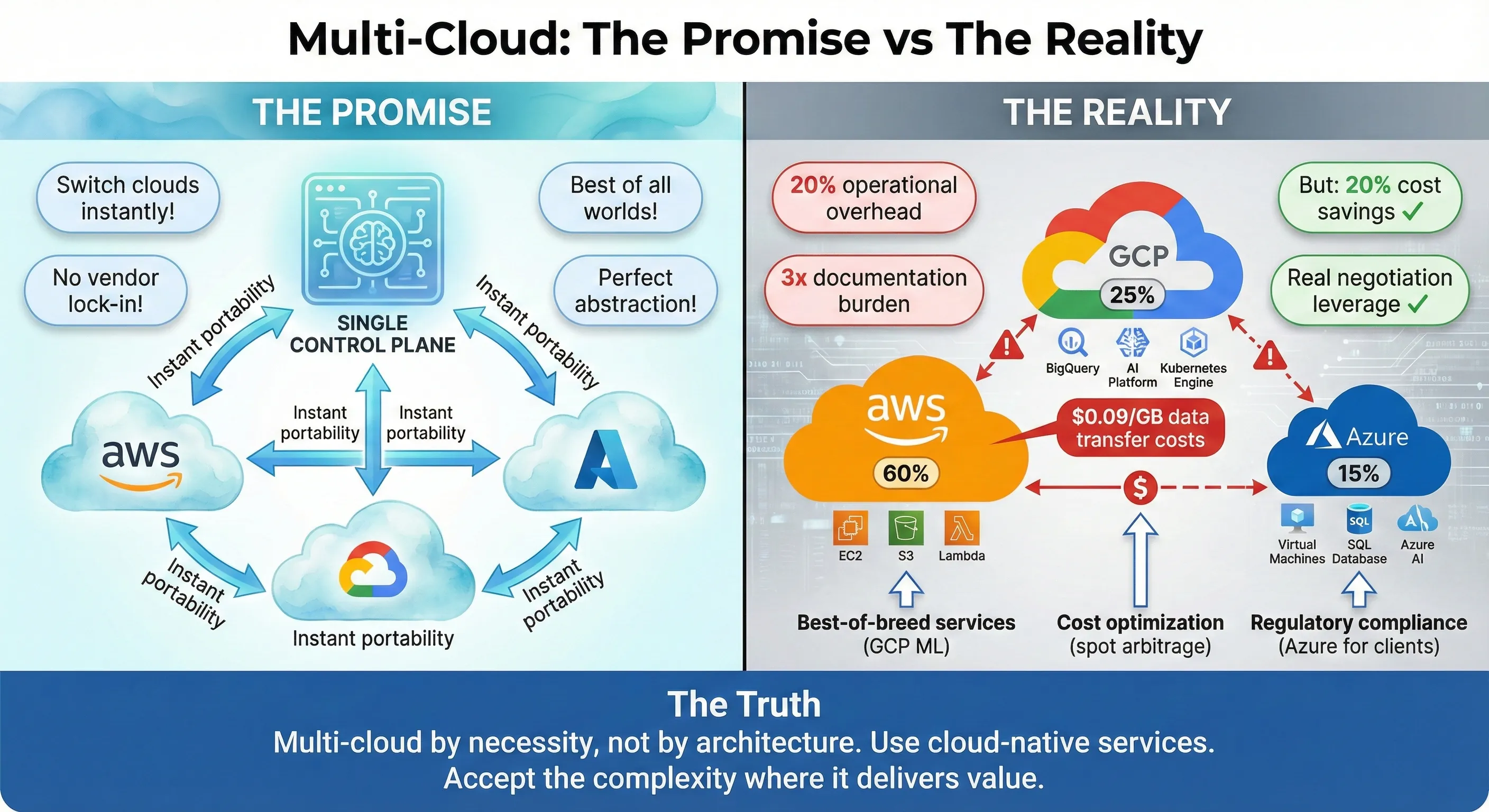

Multi-Cloud: The Promise vs The Reality

Production incidents at 3am don't care which cloud you run on. Last year, we ran infrastructure across AWS, Azure, and GCP—not because we followed some multi-cloud religion, but because business requirements forced our hand. Our primary workloads lived on AWS, our ML platform needed GCP's superior AI capabilities, and several enterprise clients contractually required Azure for Microsoft stack integration. The result? We achieved 20% cost savings through optimal workload placement, maintained negotiating leverage with vendors, and avoided the vendor lock-in trap—all without building a complex abstraction layer that would've tripled our engineering overhead.

Here's what I didn't do: I didn't build a custom abstraction layer to make every service "cloud-portable." I didn't avoid managed services out of lock-in fear. I didn't force Kubernetes on workloads that didn't need it. And I certainly didn't chase the dream of running identical workloads across all three clouds simultaneously.

The multi-cloud conversation has become polluted with two extremes. On one side, you have the zealots who insist every company needs multi-cloud architecture from day one, building elaborate abstraction layers to avoid any cloud-specific features. On the other, you have the single-cloud purists who dismiss multi-cloud as resume-driven complexity with no business value. Both are wrong. After managing infrastructure budgets exceeding $5M annually and deploying systems handling 100K+ requests per second across multiple clouds, I've learned that the truth lives in the pragmatic middle ground.[1]

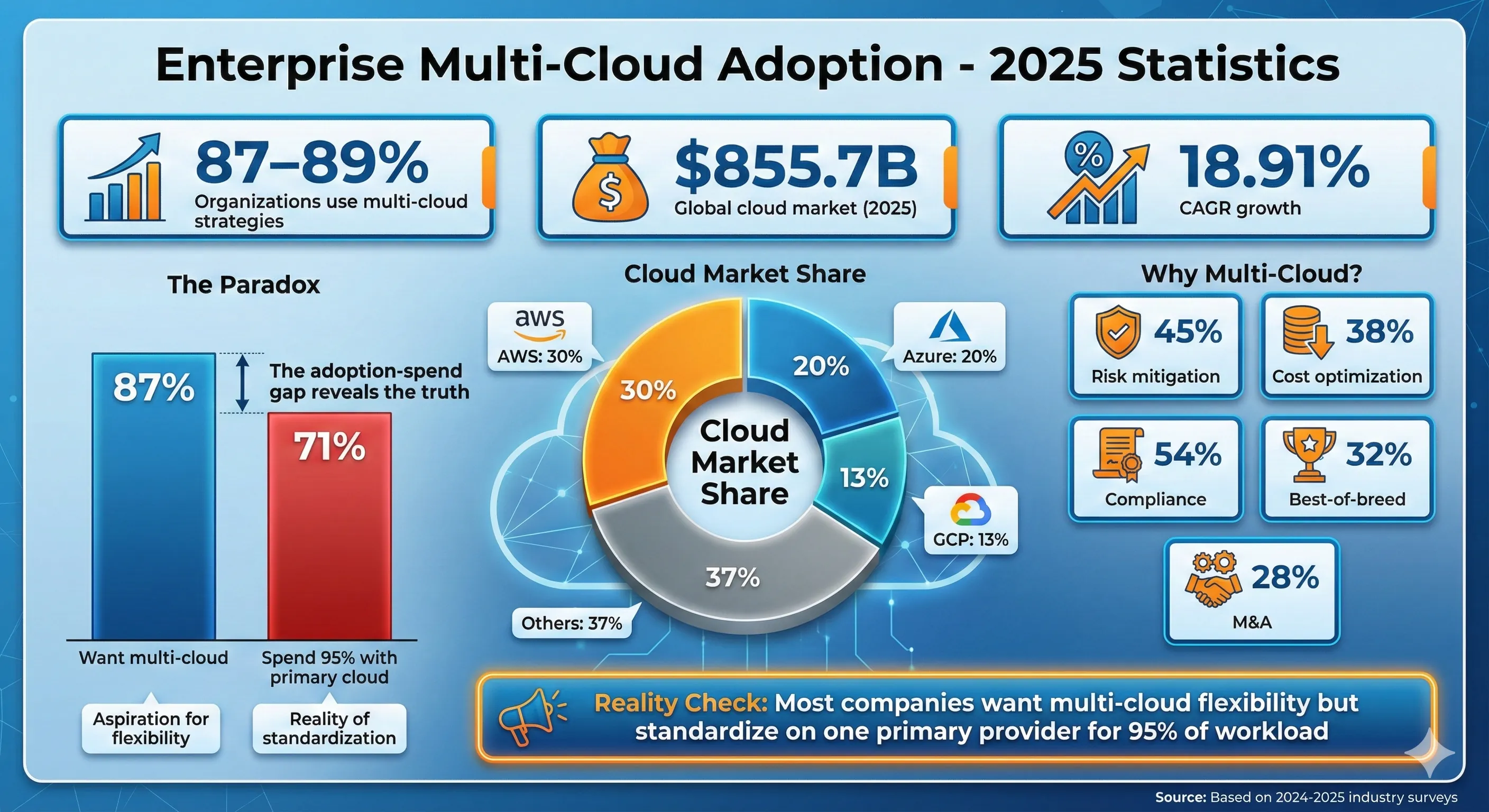

The vendor lock-in fear is real but often misunderstood. According to 2024 research, 92% of enterprises have adopted multi-cloud strategies, yet the same research shows that most companies still spend 95% of their cloud budget with a single primary provider. This disconnect reveals a critical insight: companies want multi-cloud flexibility, but few actually need perfect portability across clouds. The question isn't whether vendor lock-in exists—it does. The question is whether the cost of avoiding it upfront exceeds the cost of migrating if you ever need to.[2][1]

My thesis is simple: Multi-cloud should emerge from business requirements, not architectural ideology. Use cloud-native managed services without guilt. Kubernetes provides portability where it matters—compute workloads—but don't extend that abstraction to databases, storage, or platform services where cloud-specific implementations deliver 10x more value. Build for the problems you have today, not the theoretical migration you might need in five years.

The results speak louder than architecture diagrams. Over 18 months managing our multi-cloud infrastructure, we reduced overall cloud costs by 20% through workload optimization—running ML jobs on GCP's cheaper GPU instances while keeping latency-sensitive APIs on AWS's broader global footprint. We leveraged our credible multi-cloud posture to negotiate better rates with AWS, securing an additional 15% discount on our Enterprise Support contract. Most importantly, we maintained engineering velocity: our deployment frequency stayed at 50+ deploys per day, and our MTTR remained under 15 minutes. The complexity we added was bounded, measurable, and worth the trade-offs.[3]

This article shares the framework I used to make pragmatic multi-cloud decisions for a 50+ person engineering team managing 200+ microservices. You'll learn when multi-cloud makes sense (and when it doesn't), how to assess actual lock-in risk versus paranoid over-engineering, and how to structure infrastructure that uses the best of each cloud without drowning in abstraction complexity. Whether you're a CTO evaluating your first multi-cloud strategy or an architect trying to reign in runaway cloud sprawl, this framework will help you make decisions based on business value, not cloud-agnostic ideology.

The Multi-Cloud Landscape

Why Organizations Consider Multi-Cloud

Enterprise Multi-Cloud Adoption - 2025 Statistics

The global cloud market reached $855.7 billion in 2025, growing at 18.91% CAGR, with AWS commanding 30% market share, Azure at 20%, and Google Cloud at 13%. Within this massive market, 87-89% of organizations now use multi-cloud strategies, making it the dominant enterprise architecture pattern. But adoption statistics tell you nothing about whether multi-cloud is right for your organization. Let's cut through the hype and examine the legitimate reasons companies go multi-cloud.[4][1]

Risk mitigation sits at the top of most CTO lists. A single cloud provider outage can take down your entire business. In my experience, this fear is both valid and overblown. Yes, AWS has had outages that took down huge portions of the internet. But the outage risk from a single cloud provider is still orders of magnitude lower than the operational risk you introduce by running active-active across multiple clouds. The complexity of cross-cloud networking, data synchronization, and failover mechanisms creates far more failure modes than it prevents. For 99% of companies, proper multi-region architecture within a single cloud provides better availability than amateur multi-cloud implementations.

Cost optimization offers more tangible value. Different clouds have different pricing for equivalent services, and the delta can be substantial. GCP's sustained-use discounts kick in automatically, while AWS requires commitment to Reserved Instances or Savings Plans. For our ML workloads, GCP's GPU pricing was 40% cheaper than AWS for P100 instances. Running batch processing jobs on GCP while keeping real-time APIs on AWS saved us $400K annually. But here's the catch: data transfer between clouds costs $0.09-$0.12 per GB, so workloads that move significant data will erase your compute savings through egress fees.[5][6][3]

Best-of-breed services represent the most compelling technical reason for multi-cloud. GCP's BigQuery is genuinely better than AWS Athena for many analytics workloads—faster, cheaper, and easier to use. GCP's Vertex AI provides superior ML platform capabilities compared to AWS SageMaker for certain use cases. Azure's Active Directory integration is unmatched if you're deep in the Microsoft ecosystem. The question is whether the operational overhead of managing multiple clouds justifies the 20-30% performance improvement of using the "best" service. For our data science team running hundreds of ML experiments monthly, GCP's superior ML tooling was worth it. For your web application that occasionally runs a SQL query, it's probably not.

Regulatory requirements force multi-cloud on many enterprises. Data sovereignty laws require certain data stay in specific geographic regions. AWS GovCloud serves U.S. government workloads with compliance requirements AWS commercial regions can't meet. Azure has unique presence in China through its partnership with 21Vianet. If you need to serve customers in these regulated environments, you're going multi-cloud whether you like it or not. This is multi-cloud by necessity, not choice—and it's a perfectly valid reason.

M&A situations create instant multi-cloud architectures. You acquire a company running entirely on Azure while your infrastructure is on AWS. Now you're multi-cloud, with zero time to plan an elegant architecture. I've been through two of these integrations. The right answer is usually "leave the acquired infrastructure alone for 12-18 months while you focus on business integration, then evaluate migration costs versus long-term multi-cloud operations." Trying to force-migrate acquired infrastructure in the first six months destroys the engineering team's productivity and derails the M&A value creation.

Negotiating leverage might be the most underrated reason for multi-cloud. When your AWS Enterprise Agreement comes up for renewal and you have credible workloads running on GCP, you're negotiating from strength. We used our 25% GCP workload allocation to negotiate an additional 15% discount on AWS Enterprise Support contracts. The cloud sales teams know when you're bluffing versus when you have real optionality. You don't need perfect portability—you need credible alternatives. According to industry data, two-thirds of CIOs say they want to avoid vendor lock-in, but 71% still standardize on one provider, spending 95% of their cloud budget there. That 5-10% spent elsewhere can provide significant negotiating power without operational chaos.[2]

Multi-Cloud vs Hybrid Cloud vs Poly-Cloud

Understanding the Multi-Cloud Terminology

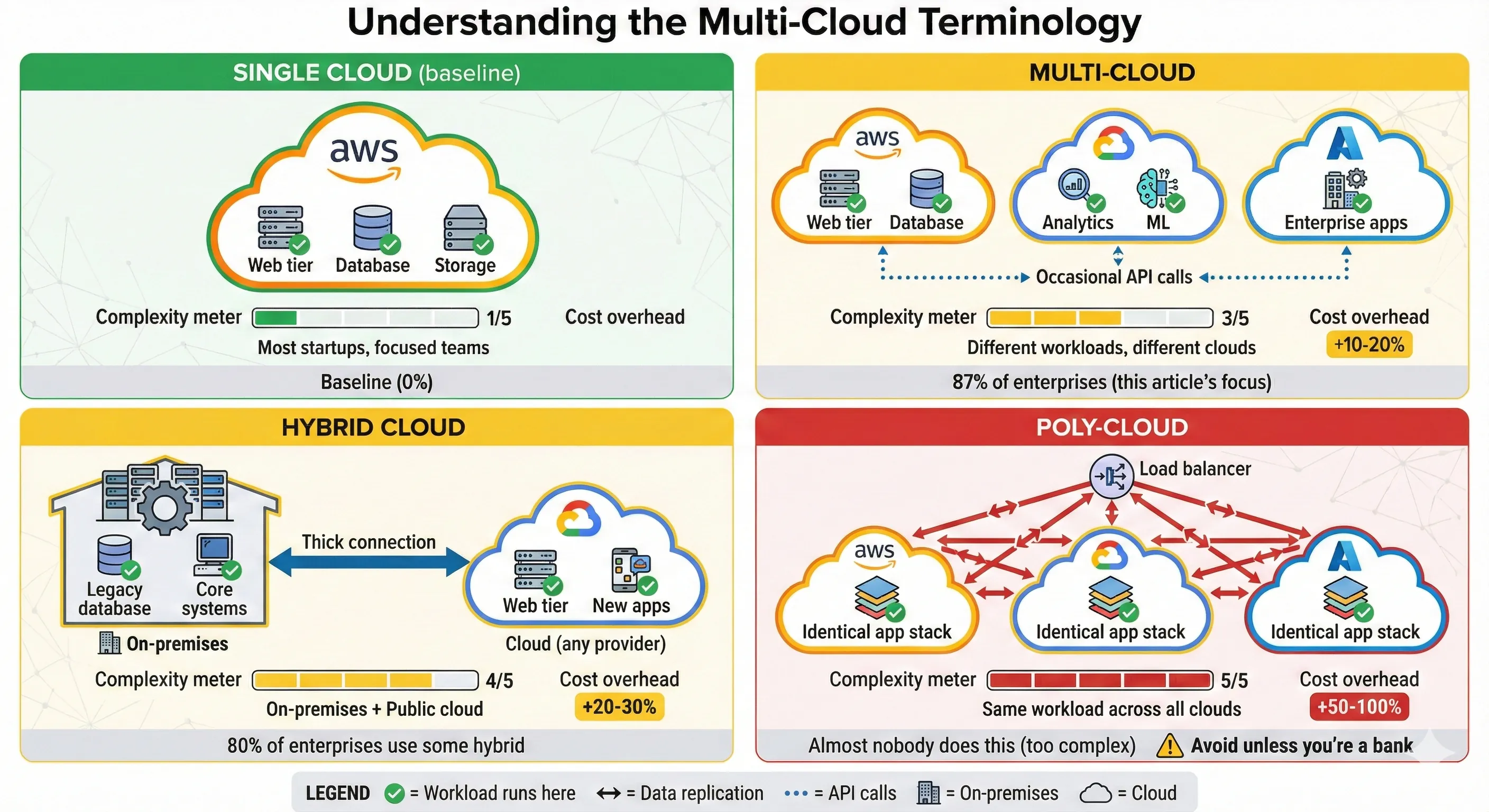

The terminology matters because different patterns have radically different complexity profiles. Let me define these terms precisely, because I've seen too many strategy documents conflate them:

Multi-cloud means using multiple public cloud providers for different workloads or purposes. Your web application runs on AWS, your analytics platform runs on GCP, your enterprise CRM integration runs on Azure. Each workload lives primarily on one cloud. There's no expectation that workloads can instantly move between clouds. This is the pragmatic pattern we implemented, and it's what 87% of enterprises actually mean when they say "multi-cloud".[1]

Hybrid cloud combines on-premises infrastructure with public cloud. Your database stays in your data center for regulatory or performance reasons, while your web tier runs in AWS. Or you run Kubernetes clusters both on-premises and in GCP, with workloads scheduled across both. Hybrid cloud is about bridging private and public infrastructure, not about using multiple public clouds. About 80% of companies use hybrid cloud in some form, up from 73% in 2023.[1]

Poly-cloud (or cloud-agnostic architecture) means running the same workload across multiple clouds simultaneously, with the ability to fail over or migrate between them quickly. This requires extensive abstraction layers and typically involves running identical infrastructure on AWS, Azure, and GCP. This is the pattern that enterprise architects draw on whiteboards and almost nobody actually implements in production. The operational complexity is massive, and the benefits rarely materialize.

Here's a comparison table showing the differences:

| Pattern | Definition | Complexity | Common Use Cases | Typical Cost Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Cloud | One provider for all workloads | Low | Most startups, focused enterprises | Baseline |

| Multi-Cloud | Different workloads on different clouds | Medium | Best-of-breed services, regulatory requirements | +10-20% operational cost |

| Hybrid Cloud | On-premises + public cloud | Medium-High | Regulated industries, data gravity | +20-30% operational cost |

| Poly-Cloud | Same workload across multiple clouds | Very High | Banks, defense contractors (rarely justified) | +50-100% operational cost |

The cost overhead isn't just money—it's engineering time, operational complexity, and cognitive load. Every additional cloud provider you support multiplies your IAM complexity, your networking setup, your monitoring tools, your compliance audits, and your on-call burden. Make sure the benefits justify the cost.

The Abstraction Trap

The Abstraction Trap: What You Lose for Portability

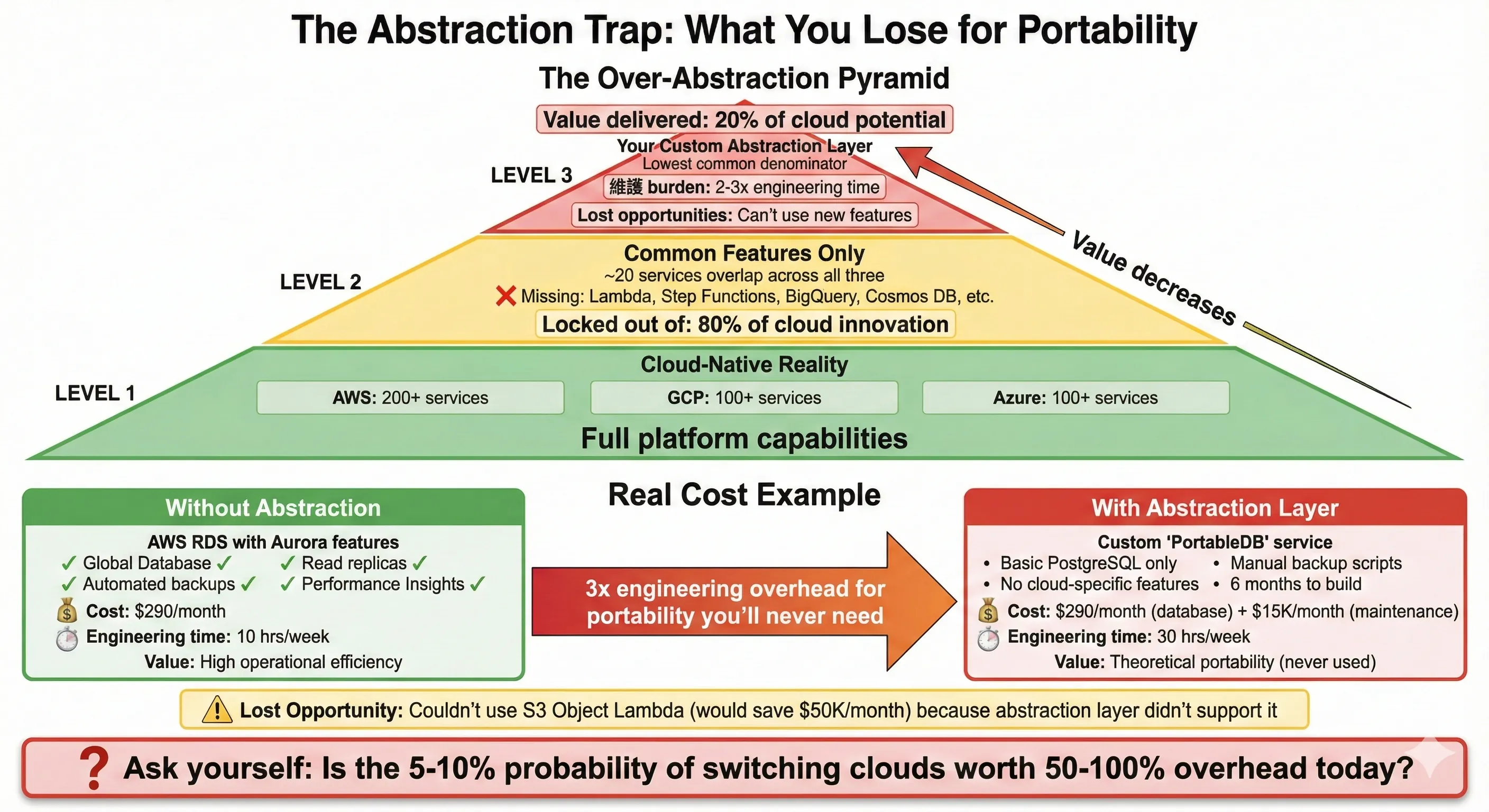

Here's where most multi-cloud strategies go wrong: over-abstraction. The thinking goes like this: "If we might need to switch clouds someday, let's build everything on abstractions so we're portable." This leads to using only the lowest common denominator features across clouds, avoiding managed services, and building elaborate internal platforms that abstract away cloud differences.

I've made this mistake. Early in my career, convinced by the vendor lock-in fear, I led a team building a custom storage abstraction layer that could work with AWS S3, Azure Blob Storage, or GCP Cloud Storage. The interface exposed only the features common to all three: GET, PUT, DELETE objects. We couldn't use S3's lifecycle policies, or Azure's cool/hot tier optimization, or GCP's signed URLs, because not all providers supported them identically. The abstraction worked—technically—but it delivered a fraction of the value of just using S3 properly.

The real cost hit us six months later. AWS launched S3 Object Lambda, which let us transform data on-read without maintaining multiple copies. This feature would've saved us $50K monthly in storage costs. But we couldn't use it—our abstraction layer didn't support it, and adding support would've violated the "portable" architecture we'd committed to. We were paying 2-3x more in engineering complexity and missing 50% of the value of managed cloud services, all for "portability" we never actually used.

The lowest common denominator problem is real. When you build abstractions to work across multiple clouds, you're constrained by the least capable provider. AWS has 200+ services, GCP has 100+, Azure has 100+. The overlap of features they all support identically is maybe 20 services. By limiting yourself to that overlap, you're ignoring 80% of the innovation these platforms provide. You're essentially paying cloud prices for features you refuse to use.

Over-abstraction kills innovation in another way: it prevents your team from learning cloud-specific capabilities. When your engineers only interact with your internal abstraction layer, they never develop deep expertise in any actual cloud platform. They can't optimize performance, can't debug issues, can't leverage new features. You've traded vendor lock-in for platform-layer lock-in to your own abstractions—which is worse, because at least cloud vendors have documentation and support.

Let me be specific about the lost opportunities. AWS Lambda, GCP Cloud Functions, and Azure Functions are all "serverless compute" platforms, but they're radically different in capabilities. Lambda's integration with AWS Step Functions enables complex workflow orchestration. GCP Cloud Functions v2 runs on Cloud Run, giving you more CPU and memory options. Azure Functions integrates tightly with Durable Functions for stateful workflows. If you abstract these into a generic "FunctionService" interface, you lose all the platform-specific power.

The same applies to databases. AWS RDS, Azure SQL Database, and GCP Cloud SQL are all "managed PostgreSQL" services, but their operational characteristics differ significantly. RDS has read replicas and Aurora's global database features. Azure SQL has built-in intelligent query performance insights. GCP Cloud SQL has automatic storage increases. Building a database abstraction that works across all three means you can't use any of these features. You end up with a managed database service that you treat like an unmanaged VM—defeating the entire point.

Here's my rule: Use cloud-native services by default. Build abstraction only when you have a concrete, imminent need to be portable. Not "we might need to switch clouds someday." Not "we want to avoid lock-in." A concrete need, like "we have regulatory requirements to run in both AWS and Azure simultaneously" or "we're actively migrating from AWS to GCP over the next 12 months." Until that concrete need exists, the cost of abstraction exceeds the benefit.

Assessment Framework

When Multi-Cloud Makes Sense

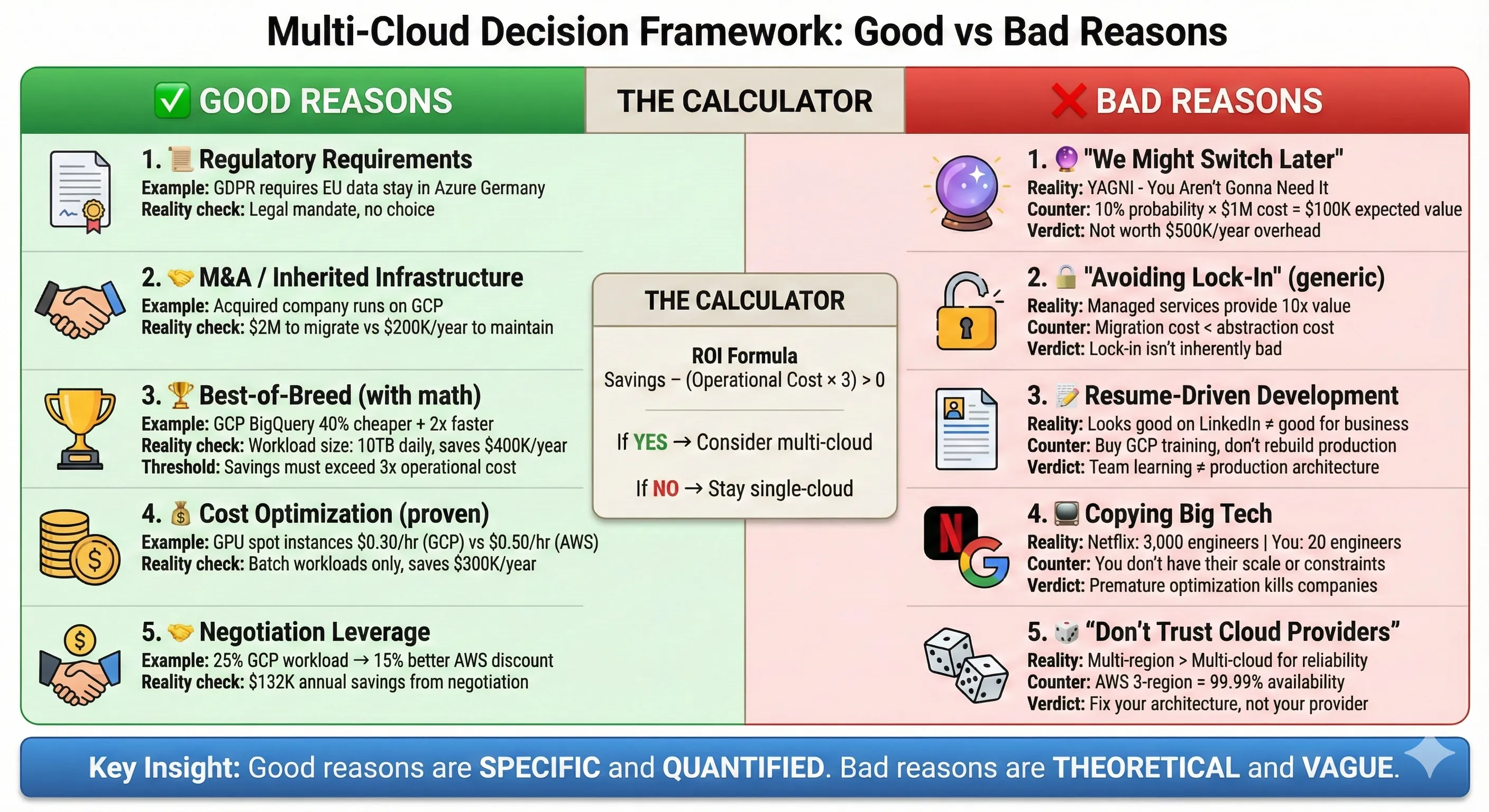

Multi-Cloud Decision Framework: Good vs Bad Reasons

Let me give you the decision framework I use when evaluating whether an organization should go multi-cloud. This framework saved us from two expensive mistakes and guided us to a pragmatic multi-cloud architecture that actually delivered value.

✅ Good Reasons for Multi-Cloud:

Regulatory and compliance requirements are the most legitimate reason to go multi-cloud. When German financial regulations require customer data stay in EU-based data centers, and Azure has better EU presence than AWS for your specific needs, you use Azure for EU customers. When U.S. government contracts require FedRAMP High compliance and only AWS GovCloud meets that requirement, you use AWS GovCloud. These aren't philosophical choices—they're legal requirements. About 54% of enterprises use hybrid or multi-cloud specifically for compliance and regulatory purposes.[1]

M&A and inherited infrastructure force multi-cloud instantly. You acquire a company running 100% on Azure, and you're on AWS. The migration cost is $2M and 12 months of engineering time. You're multi-cloud now, like it or not. The right move isn't to immediately start abstracting—it's to operate both clouds competently while gradually consolidating where business value justifies it. I went through this when we acquired a company running entirely on GCP. We kept their infrastructure on GCP for 18 months, integrated at the API level, and only migrated workloads when there was a specific business reason (cost, compliance, or operational simplification).

Best-of-breed services justify multi-cloud when the service delta is significant and the workload is substantial. GCP's BigQuery is genuinely 2-3x better than AWS Athena for many analytics workloads—faster queries, better pricing model, easier to use. If you're running a data analytics platform processing 10TB daily, that difference matters. It justified our decision to run the entire analytics platform on GCP while keeping application servers on AWS. But notice the qualifier: "workload is substantial." Using GCP's Natural Language API for one feature in your application doesn't justify multi-cloud infrastructure. Call it as a REST API and move on.

Disaster recovery and true high availability might justify multi-cloud for critical systems, but only if you've already maximized single-cloud availability. We run our payment processing system across AWS us-east-1, us-west-2, and eu-west-1 regions with automatic failover. That gives us 99.99%+ availability without touching another cloud. Adding GCP would increase availability to maybe 99.995%, but at 10x the operational complexity. For our use case, not worth it. But if you're running infrastructure for a major financial exchange where every minute of downtime costs millions, multi-cloud active-active might be justified. The bar is extremely high.

Cost optimization works for specific workload types. Spot instances, preemptible VMs, and spot VMs have different availability and pricing across clouds. Running batch processing jobs opportunistically across clouds based on current spot pricing can save 40-60% on compute costs. We did this for ML training jobs—using whichever cloud had the cheapest GPU spot instances that hour. The savings were $300K annually. But this only works for truly stateless, interruptible workloads. And you need sophisticated orchestration to make it work.

Negotiation leverage justifies a limited multi-cloud presence. Spending 5-10% of your cloud budget on a secondary provider gives you credible alternatives when negotiating your primary provider's Enterprise Agreement. We allocated 25% of workload to GCP, which gave us real leverage with AWS. The 15% additional discount we negotiated exceeded the operational cost of managing two clouds.

❌ Bad Reasons for Multi-Cloud:

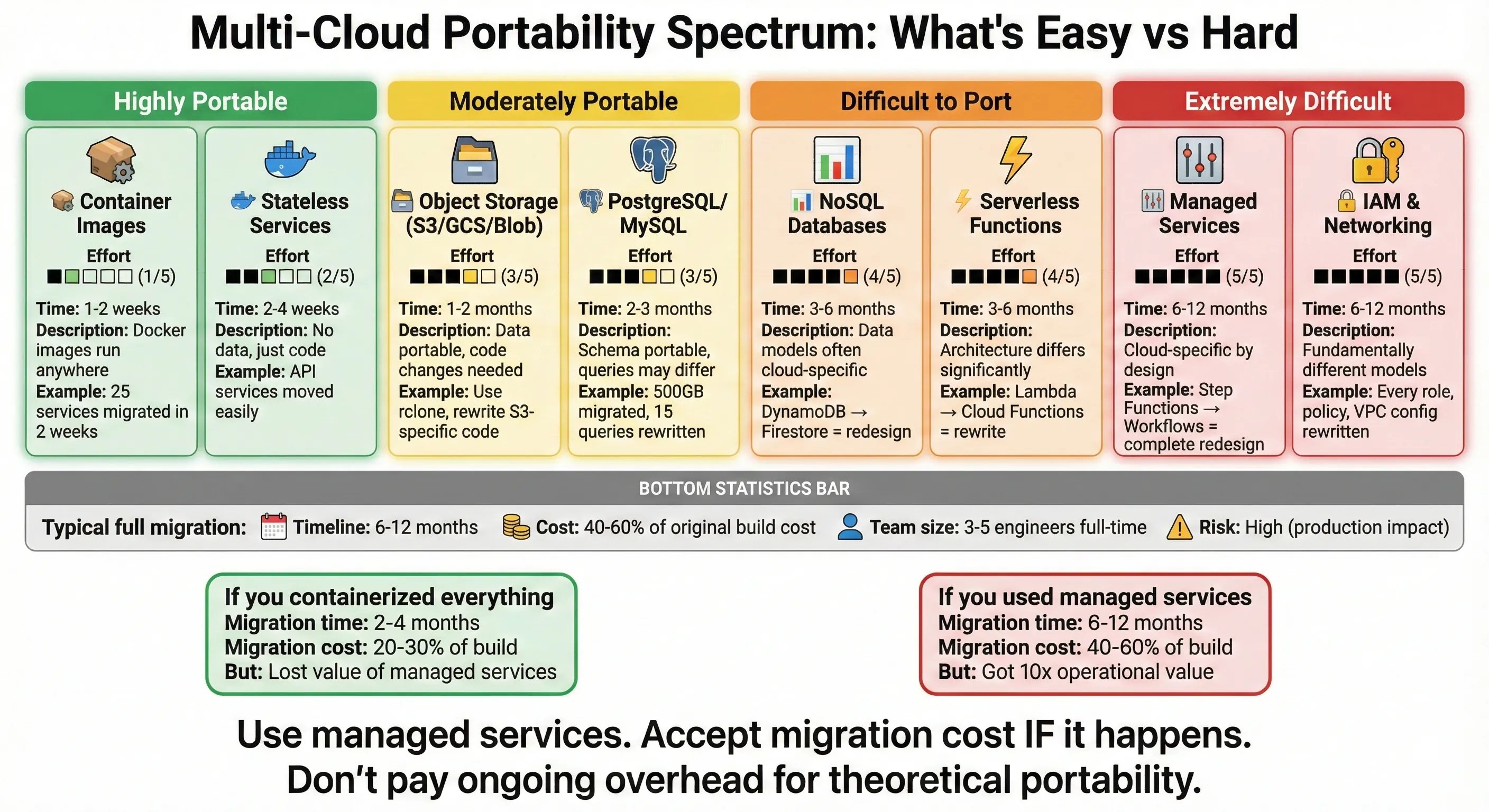

"We might want to switch clouds later" is YAGNI (You Aren't Gonna Need It) thinking. How often do companies actually switch clouds? Almost never. According to research, 71% of companies standardize on one cloud provider even when they have multi-cloud aspirations. The theoretical future optionality almost never materializes, and the upfront cost is real. If you do need to switch later, migration tools have gotten much better—AWS Database Migration Service, CloudEndure, various open-source tools. The 2024 announcement that all major cloud providers waive egress fees for customers leaving makes migration much cheaper than it used to be.[7][8][2]

"Avoiding vendor lock-in" without a specific risk assessment is paranoid architecture. Cloud providers want to keep your business, but they're not holding you hostage. The switching cost is high because you've built sophisticated infrastructure, not because of nefarious lock-in mechanisms. Using AWS RDS instead of self-managed PostgreSQL gives you massive operational value—automatic backups, automated patching, read replicas, point-in-time recovery. That value doesn't disappear because you're "locked in" to RDS. If you need to switch to GCP later, you migrate your PostgreSQL database (which is portable) and reconfigure your infrastructure. It's work, but it's not impossible.

Resume-driven development kills companies. I've seen architects push multi-cloud because it looks impressive on their LinkedIn profile, not because it solves a business problem. If your team is excited about multi-cloud because they want to learn GCP but your entire business runs fine on AWS, the answer is no. Buy them GCP training courses and sandbox accounts, don't restructure production infrastructure.

Copying Netflix/Facebook/Google without their constraints leads to disaster. Yes, Netflix runs multi-cloud. They also have 3,000+ engineers and a mature chaos engineering practice. Their scale and requirements justify multi-cloud complexity. Your 20-person engineering team does not. I've never regretted waiting to adopt a complex pattern until we genuinely needed it. I've always regretted premature complexity.

Lock-in Risk Assessment

Lock-in Risk vs Mitigation Cost Decision Matrix

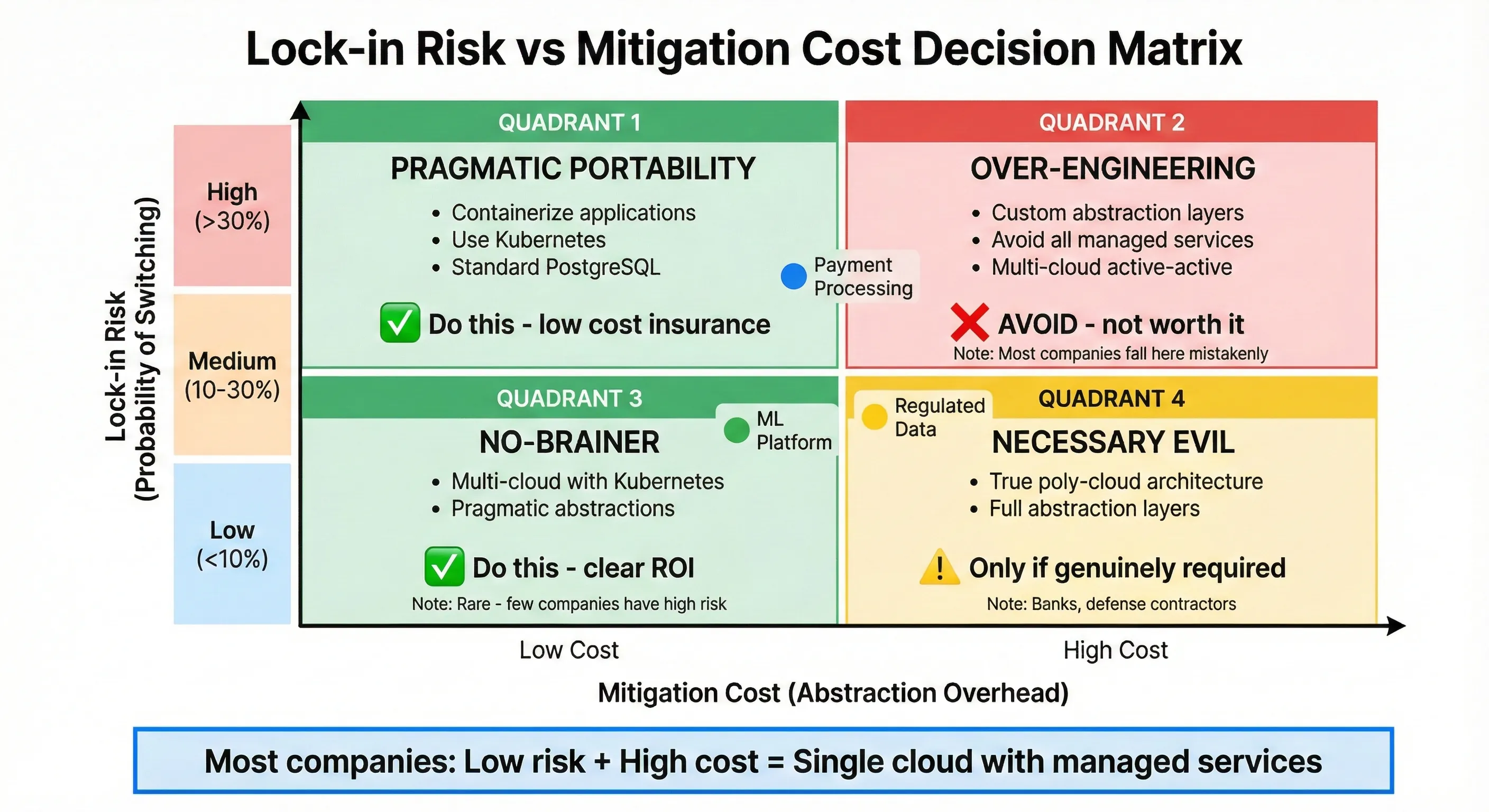

Here's the framework I use to assess actual lock-in risk versus paranoid over-engineering. This isn't about eliminating lock-in—it's about understanding whether lock-in risk justifies upfront mitigation cost.

Ask these questions honestly:

-

How likely is it we'll switch clouds? Not "is it possible," but "what's the actual probability?" For most companies, the honest answer is 5-10%. Major cloud providers have gotten more reliable and competitive. The switching cost is high. The disruption is massive. You switch clouds when you're forced to (acquisition, regulatory change, catastrophic pricing increase), not because you want to. If your honest assessment is < 10% probability, building elaborate portability isn't justified.

-

What would trigger a switch? Be specific. "AWS triples our pricing"—unlikely, they need to stay competitive. "AWS has a multi-week outage affecting us"—possible but rare, and multi-region architecture mitigates this. "We get acquired by a company standardized on Azure"—actually happens. "New regulations require data stay in Azure's specific compliance zones"—realistic. If you can't articulate specific, plausible triggers, your lock-in fear is theoretical.

-

What's the cost of switching if needed? Do the math. Migrating 200 microservices from AWS to GCP: 2 engineers × 12 months = $500K in labor. Retraining 50 engineers on GCP: $200K. Risks during migration: $500K (opportunity cost of incidents, slower feature velocity). Total: $1.2M. Now compare that to the cost of avoiding lock-in upfront: complex abstraction layers, limited feature usage, 20% operational overhead, 3 extra engineers to manage multi-cloud complexity: $600K annually. If the probability of switching is <10%, you're paying $6M over 10 years to avoid a $1.2M one-time cost. The math doesn't work.

-

What's the cost of avoiding lock-in upfront? Calculate this honestly. Operational overhead of managing multiple clouds: +20% engineering time = $400K annually for a 20-person team. Lost productivity from abstraction limitations: ~10% slower feature velocity = $300K annually in opportunity cost. Delayed features because the abstraction layer takes 6 months to build: incalculable but real. These costs are guaranteed and immediate, while the lock-in risk is probabilistic and distant.

I built a simple decision matrix for evaluating this:

| Lock-in Risk Level | Mitigation Cost | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| Low risk (<10% switching probability) | High mitigation cost | Single cloud, use managed services freely |

| Low risk | Low mitigation cost | Mild portability practices (containerization) |

| Medium risk (10-30% probability) | Low mitigation cost | Multi-cloud with pragmatic abstractions |

| Medium risk | High mitigation cost | Single cloud, accept migration cost if it happens |

| High risk (>30% probability) | High mitigation cost | True multi-cloud with abstraction layers |

| High risk | Low mitigation cost | Multi-cloud with abstraction layers |

Most companies fall into "low risk, high mitigation cost"—use a single cloud aggressively. Some fall into "low risk, low mitigation cost"—containerize workloads for mild portability. Almost nobody has "high risk"—even companies that think they do usually don't when they assess honestly.

Our specific assessment: We evaluated each major system:

- Payment processing (AWS): Low risk (5% switching probability), high value from AWS's mature payment integrations. Decision: Stay on AWS, use RDS/Lambda/DynamoDB freely.

- ML platform (GCP): Medium risk (20% probability we'd consolidate to AWS), but huge value from BigQuery/Vertex AI today. Decision: Run on GCP, accept potential future migration cost.

- Enterprise client workload (Azure): High risk (50% probability client cancels, forcing consolidation), but contractually required. Decision: Keep isolated on Azure, don't integrate deeply.

This framework led to our pragmatic multi-cloud architecture—not because we wanted to be multi-cloud, but because business requirements pulled us there.

Workload Placement Strategy

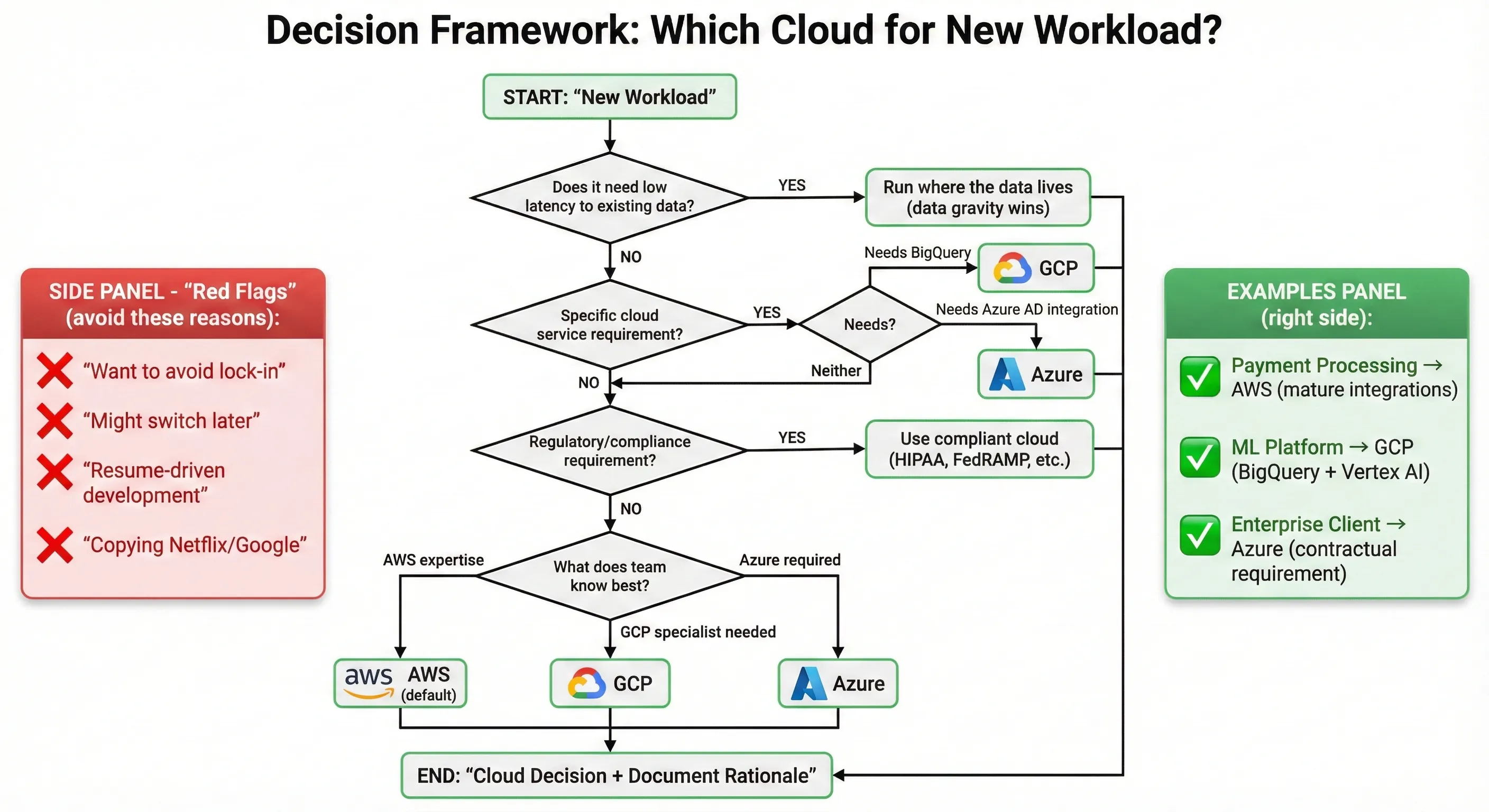

Decision Framework: Which Cloud for New Workload?

Not all workloads need to be portable. Not all workloads should be on the same cloud. Here's the classification framework I use for making workload placement decisions:

Cloud-Native Critical Workloads: These are your core business systems where reliability, performance, and operational simplicity matter most. Use the full power of your primary cloud provider—managed databases, serverless functions, managed Kubernetes, platform services. Don't apologize for lock-in. The value of RDS's automated backups, Lambda's instant scaling, and DynamoDB's single-digit millisecond latency exceeds the theoretical portability benefit. Our payment processing system, user authentication system, and main application APIs all fall here. They're AWS-native, they use AWS-specific features, and they're better for it.

Portable Compute Workloads: These are stateless or near-stateless services that run in containers and don't depend heavily on cloud-specific platform services. They're good candidates for Kubernetes, and naturally portable across clouds. Our internal tools, batch processing jobs, and some microservices fall here. We run them on EKS (AWS managed Kubernetes), but the container images would run identically on GKE or AKS with minimal changes. This portability is a nice side effect of containerization, not the primary goal.

Specialized Workloads: Some workloads genuinely need specific cloud capabilities. Our analytics platform needs BigQuery's performance and cost model—no AWS alternative comes close for our use case. This lives on GCP and uses GCP-native services without guilt. Our enterprise clients with Microsoft stack requirements need Azure's AD integration and specific compliance certifications. Those workloads live on Azure. This is multi-cloud by necessity, but each workload is fully cloud-native on its chosen platform.

Experimental and Innovation Workloads: New projects, prototypes, and R&D systems should use whatever tools best accelerate learning. Don't burden innovation with portability requirements. We let teams choose their cloud for new projects based on what they want to learn or what best fits the use case. Many prototypes die—the ones that succeed can be migrated if needed. Optimizing dead prototypes for portability is waste.

Regulated Workloads: Healthcare data, financial data, government data—these follow compliance requirements first, architecture principles second. If HIPAA compliance requires specific Azure configurations, or FedRAMP requires AWS GovCloud, that's where the workload goes. Architecture purity doesn't override legal requirements.

Here's a workload classification table showing our actual placement decisions:

| Workload | Type | Cloud | Rationale | Lock-in Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Processing | Cloud-Native Critical | AWS | Mature integrations, RDS Aurora | Low - value exceeds risk |

| User Authentication | Cloud-Native Critical | AWS | Cognito integration, DynamoDB | Low - well-understood migration path |

| Main API Services | Cloud-Native Critical | AWS | Lambda/API Gateway stack | Low - core competency |

| Analytics Platform | Specialized | GCP | BigQuery performance + cost | Medium - but justified by value |

| ML Training Jobs | Portable Compute | GCP/AWS | Spot instance arbitrage | None - truly portable |

| Enterprise Client Apps | Regulated | Azure | Contractual requirement | High - but temporary |

| Internal Tools | Portable Compute | AWS (EKS) | Containerized, stateless | None - naturally portable |

The key insight: Make workload placement decisions based on business value and technical fit, not portability theology. Lock-in risk is just one factor among many—performance, cost, team expertise, regulatory requirements, and time-to-market often matter more.

Pragmatic Multi-Cloud Architecture

Your Multi-Cloud Setup

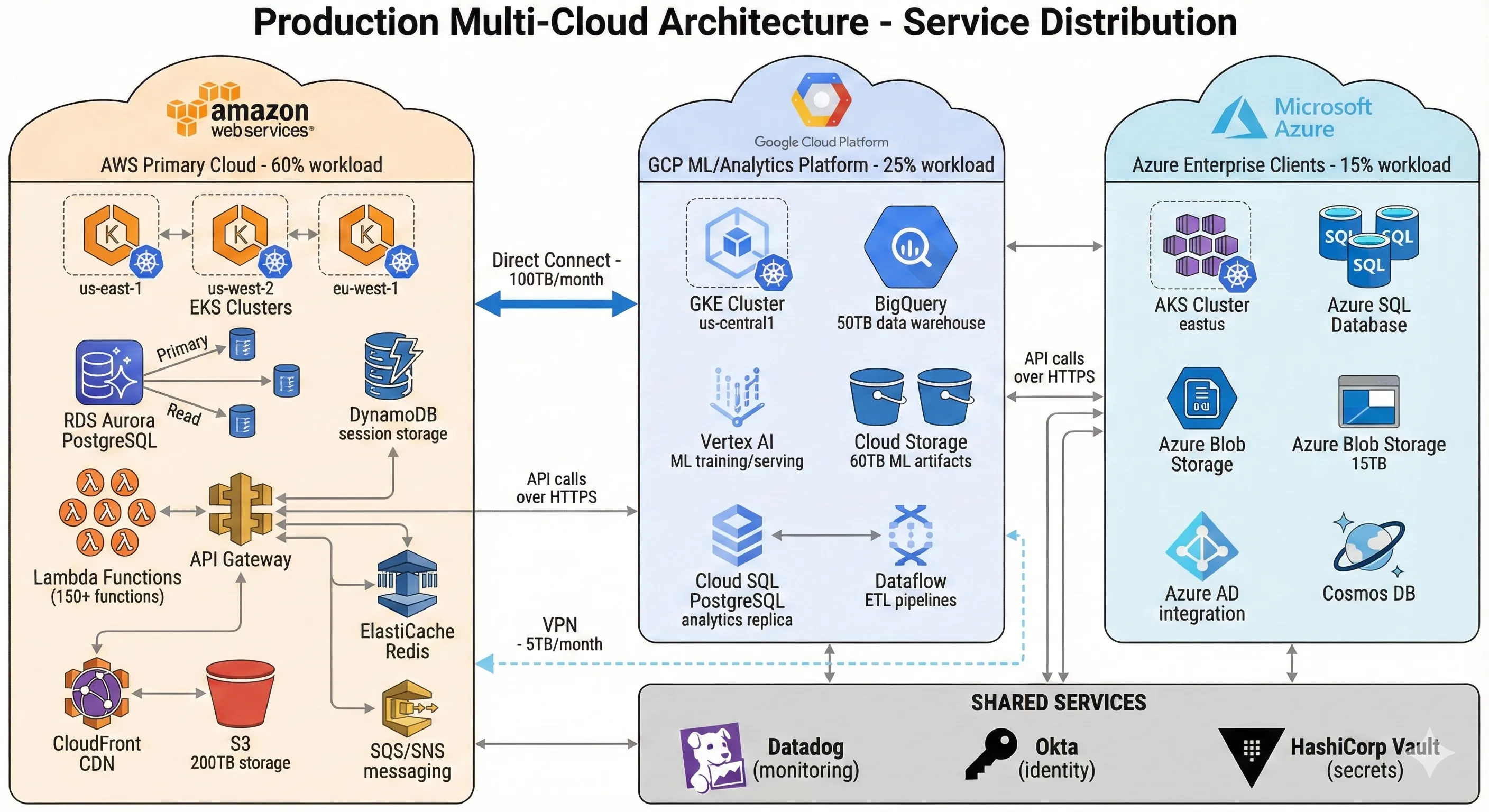

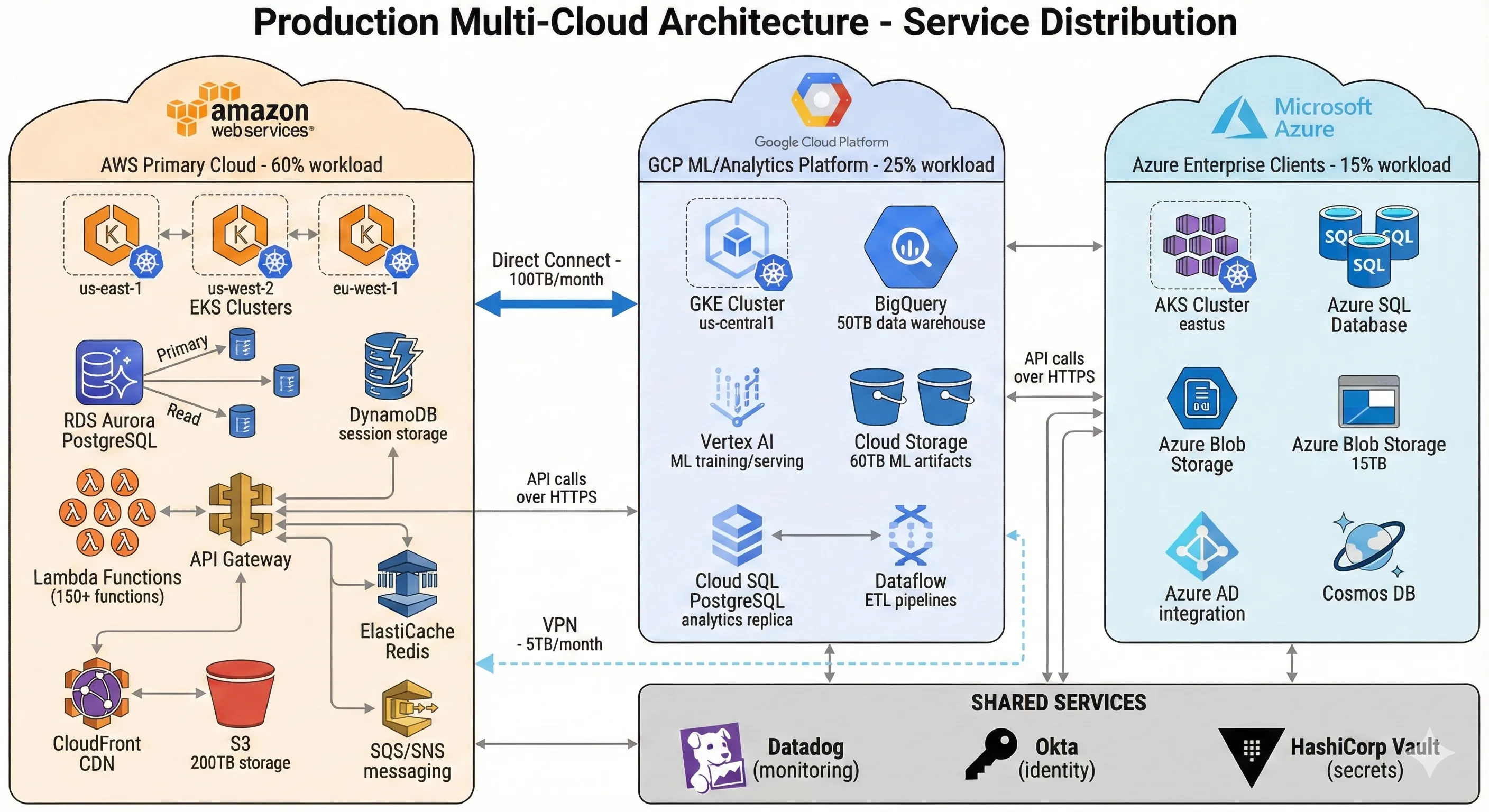

Production Multi-Cloud Architecture - Service Distribution

Let me show you the actual architecture we built, with real numbers and specific services. This isn't theoretical—it's the production system serving millions of requests daily across three clouds.

AWS (60% of workload, 55% of spend): This is our primary cloud. Core application servers, main databases, user authentication, payment processing, and most microservices run here. We use AWS-native services aggressively: RDS Aurora for PostgreSQL (primary database), DynamoDB for session storage, Lambda for event-driven workflows, SQS/SNS for messaging, API Gateway for external APIs, CloudFront for CDN, and EKS for containerized microservices. We're not trying to be portable—we're using managed services that save us 50+ engineering hours weekly compared to self-managed alternatives.[1]

GCP (25% of workload, 23% of spend): Our entire analytics and ML platform lives here. BigQuery stores 50TB of analytics data and handles 2,000+ queries daily. Vertex AI runs ML model training and serving. Cloud Storage holds training data and model artifacts. GKE runs our ML inference services. We chose GCP for this workload because BigQuery's performance and pricing beat AWS Athena/Redshift by 40% for our specific query patterns, and GCP's GPU spot instance pricing is 35% cheaper than AWS. This isn't premature optimization—it's $400K annual savings on a platform serving 30 data scientists.[3]

Azure (15% of workload, 22% of spend): We have three enterprise clients whose contracts require Azure for compliance and Microsoft stack integration. Their workloads run on Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS), Azure SQL Database, and Azure Blob Storage. We maintain Azure AD integration for SSO. This is our least favorite cloud (higher costs, less mature tooling), but it's contractually required. The workloads are isolated from our other infrastructure—they communicate via public APIs only. Azure's higher cost reflects premium pricing for enterprise compliance features and our lower utilization scale (fixed costs spread over smaller workload).

Service distribution breakdown:

- Compute: 120 microservices on AWS EKS, 40 services on GCP GKE, 25 services on Azure AKS

- Databases: 8 RDS instances (AWS), 2 Cloud SQL instances (GCP), 3 Azure SQL instances (Azure), plus BigQuery (GCP) and DynamoDB tables (AWS)

- Storage: 200TB on S3 (AWS), 60TB on Cloud Storage (GCP), 15TB on Azure Blob Storage

- Serverless: 150+ Lambda functions (AWS), 30 Cloud Functions (GCP), 10 Azure Functions

- Data pipeline: Kafka on AWS MSK, GCP Dataflow for ETL, Azure Data Factory for enterprise clients

Decision criteria for placement: We ask four questions when deciding where to run a new workload:

- Does it need low latency to existing data? If yes, run it where the data lives. Data gravity wins—moving compute is cheaper than moving data at scale.

- Does it have specific cloud service requirements? If it needs BigQuery, it's on GCP. If it needs specific Azure AD integrations, it's on Azure. If neither, default to AWS.

- What does the team know? Our primary team expertise is AWS. New engineers learn AWS first. GCP and Azure are specialist areas.

- What's the regulatory posture? Compliance requirements override technical preferences.

This isn't elegant. It's not "cloud-agnostic." But it works, it's maintainable, and it delivers business value without drowning in abstraction complexity.

Kubernetes as Portability Layer

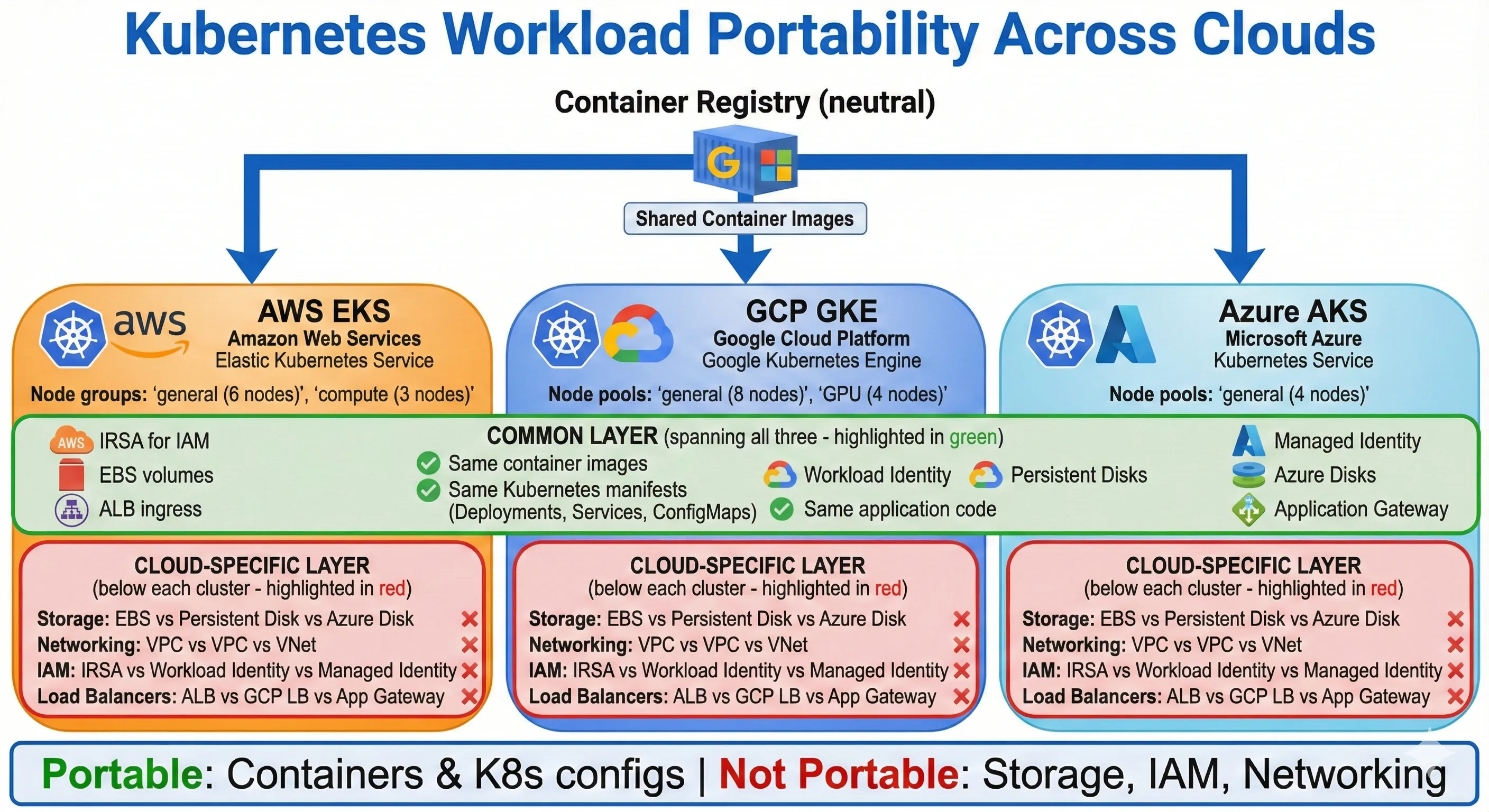

Kubernetes Workload Portability Across Clouds

Kubernetes provides natural portability for containerized workloads—emphasis on "natural." We use Kubernetes because it's a good container orchestration platform, not because we're building cloud-agnostic architecture. The portability is a side effect, not the goal.

We run managed Kubernetes on all three clouds: EKS on AWS, GKE on GCP, AKS on Azure. We don't abstract the Kubernetes implementation itself—each managed service has specific features and configurations, and we use them. EKS's IAM integration for service accounts is AWS-specific and powerful. GKE's Workload Identity and Autopilot mode are GCP-specific and valuable. AKS's Azure AD integration matters for our enterprise clients. Trying to abstract these would lose significant value.

What's actually portable: Our container images run identically across all three Kubernetes clusters. Same Dockerfile, same CI/CD pipeline, same container registry (we use Google Container Registry as a neutral zone, but we could use any registry). Application code doesn't know or care which cloud it's on. Environment configuration comes from Kubernetes ConfigMaps and Secrets, which are cloud-agnostic.

What's cloud-specific: Storage (EBS volumes vs Persistent Disks vs Azure Disks), networking (VPCs, security groups, firewalls), IAM (service account authentication), ingress controllers (AWS ALB vs GCP Load Balancer vs Azure Application Gateway), and everything outside Kubernetes (databases, message queues, object storage). We don't try to abstract these—we use cloud-native implementations and accept the cloud-specific configuration.

Here's a production Kubernetes deployment that works across all our clouds with minimal changes:

# deployment.yaml - Core app deployment

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: user-service

namespace: production

labels:

app: user-service

version: v2.4.1

spec:

replicas: 6

selector:

matchLabels:

app: user-service

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: user-service

version: v2.4.1

spec:

serviceAccountName: user-service-sa

containers:

- name: user-service

image: gcr.io/company/user-service:v2.4.1

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

name: http

env:

- name: DATABASE_URL

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: database-creds

key: connection-string

- name: CACHE_ENDPOINT

valueFrom:

configMapKeyRef:

name: app-config

key: redis-endpoint

- name: ENVIRONMENT

value: "production"

resources:

requests:

cpu: "500m"

memory: "1Gi"

limits:

cpu: "2000m"

memory: "2Gi"

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /health

port: 8080

initialDelaySeconds: 30

periodSeconds: 10

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /ready

port: 8080

initialDelaySeconds: 5

periodSeconds: 5

---

# service.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: user-service

namespace: production

spec:

selector:

app: user-service

ports:

- port: 80

targetPort: 8080

protocol: TCP

type: ClusterIP

This deployment runs identically on EKS, GKE, and AKS. The cloud-specific parts—like how the service account authenticates to cloud resources, or how the load balancer gets created—are configured separately via cloud-specific annotations and Terraform.

The networking layer is where cloud differences matter most. We use Istio service mesh for cross-cluster communication when needed, but sparingly. Most services stay within their cloud. When a service on AWS needs to call a service on GCP, it goes through public APIs with proper authentication. We don't try to create a flat network across clouds—the complexity and cost (VPN or direct connections) aren't justified by our occasional cross-cloud traffic.

Architecture principle: Kubernetes gives us portability for compute workloads. We use it. But we don't extend that portability mindset to data, storage, networking, or platform services. The cost of abstracting those exceeds the benefit.

Data Strategy Across Clouds

Data is the hardest part of multi-cloud architecture. Moving data between clouds is expensive ($0.09-$0.12 per GB egress), slow, and operationally complex. Our data strategy follows one principle: Keep data and compute together.[6][5]

Data gravity is real. Once you have 50TB of data in AWS S3, running compute jobs against that data in GCP means paying $4,500-$6,000 in data transfer costs just to move it once. If you're running daily jobs, that's $150K monthly—more than most compute costs. Data should stay where it lands, and compute should come to the data, not the other way around.

We use cloud-native databases on each cloud—no attempts at database portability. On AWS: RDS Aurora for PostgreSQL (transactional data), DynamoDB for key-value data, ElastiCache for Redis (caching). On GCP: Cloud SQL for PostgreSQL (analytics source data), BigQuery (data warehouse), Firestore (document data for ML platform). On Azure: Azure SQL Database (enterprise client data), Cosmos DB (one client's specific requirement). Each database uses cloud-specific features that make it better—Aurora's Global Database for multi-region replication, BigQuery's automatic clustering and partitioning, Cosmos DB's multi-model capabilities.

When we replicate data across clouds: Only for disaster recovery and specific analytics requirements. Our primary PostgreSQL database on AWS RDS Aurora replicates to a read replica in GCP Cloud SQL using logical replication. This backup costs us $2,000 monthly in cross-cloud data transfer (we replicate about 20GB of daily changes). We do this because the GCP replica serves our analytics workloads—the data science team queries it for ML feature engineering without impacting production database performance. The $2,000 monthly cost is justified by avoiding production database load and having a cross-cloud disaster recovery option.[6]

For real-time data replication at scale, we use Debezium for Change Data Capture (CDC). Debezium monitors our AWS RDS PostgreSQL database and streams changes to Kafka (running on AWS MSK). From Kafka, we can route data to GCP BigQuery for analytics or to Azure for enterprise client reporting. Here's the Debezium connector configuration:

{

"name": "postgres-cdc-connector",

"config": {

"connector.class": "io.debezium.connector.postgresql.PostgresConnector",

"database.hostname": "production-db.cluster-abc123.us-east-1.rds.amazonaws.com",

"database.port": "5432",

"database.user": "debezium_user",

"database.password": "${CDC_DB_PASSWORD}",

"database.dbname": "production",

"database.server.name": "production-db",

"table.include.list": "public.users,public.orders,public.transactions",

"plugin.name": "pgoutput",

"publication.name": "debezium_publication",

"slot.name": "debezium_slot",

"heartbeat.interval.ms": "10000",

"transforms": "route",

"transforms.route.type": "org.apache.kafka.connect.transforms.RegexRouter",

"transforms.route.regex": "([^.]+)\\.([^.]+)\\.([^.]+)",

"transforms.route.replacement": "$3"

}

}

From Kafka, a GCP Dataflow job consumes the change stream and writes to BigQuery. This architecture costs us about $5,000 monthly in data transfer and infrastructure, but it enables real-time analytics on GCP while keeping our transactional database on AWS. The alternative—querying AWS RDS directly from GCP—would slow our analytics queries and risk impacting production database performance.

Object storage strategy: We use cloud-native object storage (S3, Cloud Storage, Azure Blob) without abstraction. Files uploaded to AWS stay on S3. ML training data on GCP stays in Cloud Storage. We don't replicate object storage across clouds unless there's a specific need. When there is—like serving static assets globally—we use CloudFront (AWS's CDN) in front of S3, which reduces egress costs by 60% compared to direct S3 access.[6]

The hardest lesson I learned: Don't try to unify data across clouds. Every attempt we made to build a "single source of truth" spanning multiple clouds resulted in complex, fragile systems with hidden costs. Instead, accept that data lives in multiple places, build clear pipelines for moving data when needed, and keep each cloud's data architecture cloud-native.

Networking & Connectivity

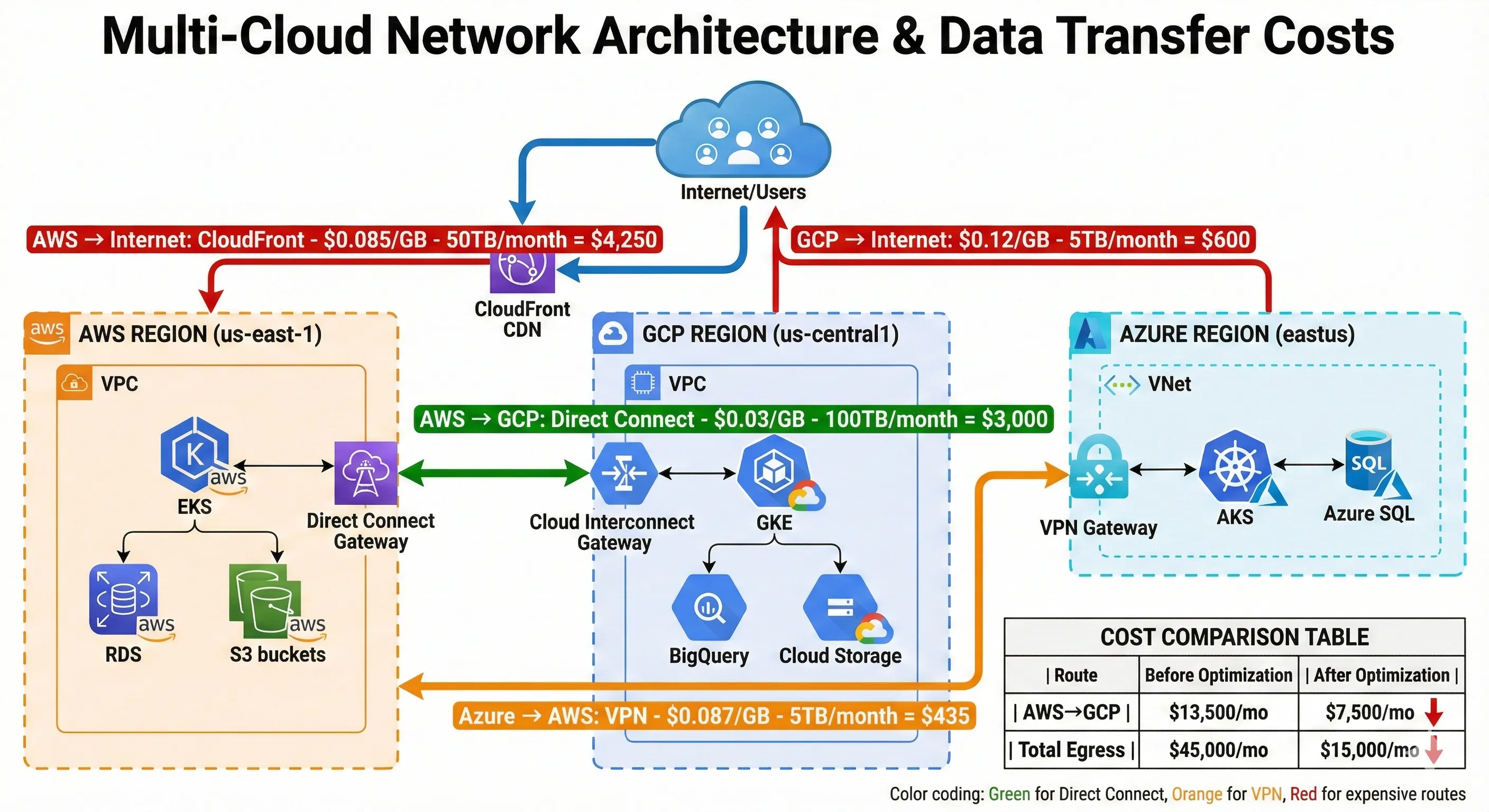

Multi-Cloud Network Architecture & Data Transfer Costs

Cross-cloud networking is expensive and complex. We keep it minimal. Most services communicate within their cloud. When cross-cloud communication is necessary, we use public APIs with proper authentication—no attempt to build a flat network spanning clouds.

For low-latency, high-volume cross-cloud communication, we use dedicated connections: AWS Direct Connect, GCP Cloud Interconnect, and Azure ExpressRoute. We set these up between AWS us-east-1 and GCP us-central1 because our ML platform on GCP frequently needs to fetch data from AWS S3. The dedicated connection costs $3,000 monthly (connection fees plus data transfer), but it's faster than public internet and slightly cheaper than public internet egress rates at our volume (about 100TB monthly).[6]

For occasional cross-cloud communication, we use VPN tunnels. Our Azure environment connects to AWS via site-to-site VPN. This costs $150 monthly and handles about 5TB monthly transfer. The VPN is fine for this volume—setting up ExpressRoute wasn't justified.

Data transfer costs are the hidden multi-cloud killer. Here's what we pay monthly:

| Route | Volume | Cost per GB | Monthly Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWS → Internet (via CloudFront) | 50TB | $0.085 | $4,250 |

| AWS → GCP (Direct Connect) | 100TB | $0.03 | $3,000 |

| GCP → Internet | 5TB | $0.12 | $600 |

| Azure → AWS (VPN) | 5TB | $0.087 | $435 |

| Total Egress | 160TB | - | $8,285 |

We optimized these costs down from $15,000 monthly by:

- Using CloudFront CDN in front of S3, reducing direct S3 egress by 60%

- Setting up Direct Connect for high-volume AWS→GCP traffic, saving $6,000 monthly compared to public internet rates

- Aggressive caching to reduce cross-cloud API calls by 40%

- Moving some ML training data directly to GCP Cloud Storage instead of pulling from S3 repeatedly

Service mesh for cross-cloud: We evaluated Istio for cross-cloud service communication but decided against it. The complexity of running Istio across three Kubernetes clusters in different clouds, managing certificates, and debugging network issues wasn't worth it for our occasional cross-cloud traffic. Instead, we use service-to-service authentication with API keys and mutual TLS, and we accept that cross-cloud calls are "external" calls—over public internet, properly authenticated, with retries and circuit breakers.

Networking principle: Cross-cloud networking is expensive and complex. Minimize it. Keep services and data within their cloud. When cross-cloud communication is necessary, use the simplest approach that works—usually public APIs with authentication, occasionally dedicated connections for high volume.

Identity & Access Management

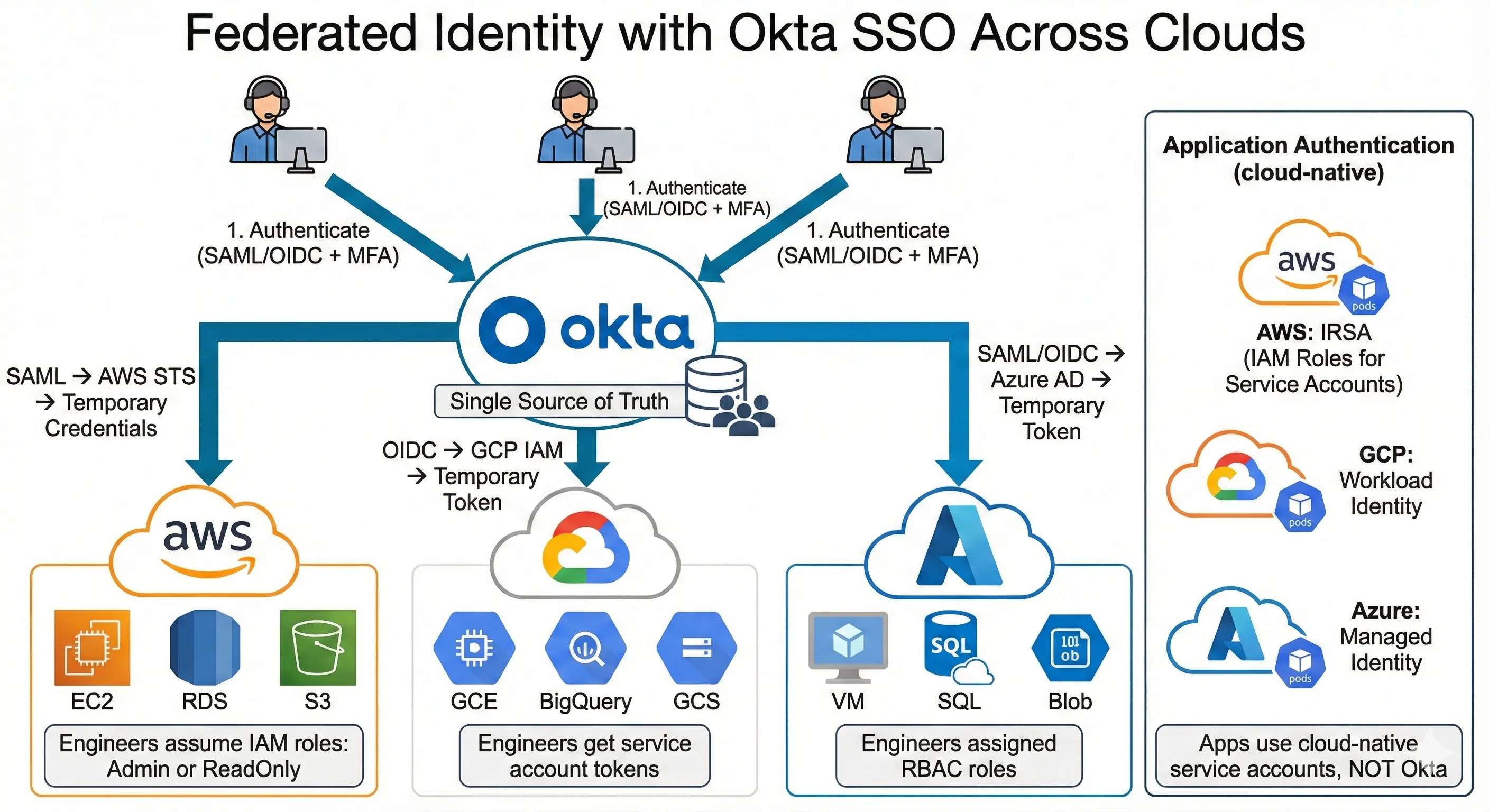

Federated Identity with Okta SSO Across Clouds

IAM across multiple clouds is a nightmare if you try to unify it. We don't. Instead, we use federated identity with our corporate SSO (Okta) as the universal identity provider, and cloud-specific IAM for resource access.

How it works: Engineers authenticate to Okta. Okta federates identity to AWS via SAML, to GCP via OIDC, and to Azure via SAML/OpenID Connect. Each cloud's IAM system trusts Okta as an identity provider. This gives engineers single sign-on to all three cloud consoles without managing separate credentials.

Here's the architecture:

- Engineer logs into Okta (username + password + MFA)

- Engineer clicks "AWS Console" in Okta app portal

- Okta sends SAML assertion to AWS STS (Security Token Service)

- AWS STS issues temporary credentials based on user's group membership

- Engineer accesses AWS console with temporary admin or read-only role

- Same process for GCP (via OIDC) and Azure (via SAML)

Cloud-specific IAM for applications: Our microservices don't use federated identity—they use cloud-native service accounts. On AWS, pods use IRSA (IAM Roles for Service Accounts) to assume IAM roles with specific permissions. On GCP, pods use Workload Identity to authenticate as service accounts. On Azure, pods use Managed Identity. These are cloud-specific mechanisms, and we don't try to abstract them.

Here's an example of AWS IRSA configuration via Terraform:

# Create IAM role for Kubernetes service account

resource "aws_iam_role" "user_service_role" {

name = "user-service-role"

assume_role_policy = jsonencode({

Version = "2012-10-17"

Statement = [{

Effect = "Allow"

Principal = {

Federated = "arn:aws:iam::${data.aws_caller_identity.current.account_id}:oidc-provider/${data.aws_eks_cluster.main.identity[0].oidc[0].issuer}"

}

Action = "sts:AssumeRoleWithWebIdentity"

Condition = {

StringEquals = {

"${data.aws_eks_cluster.main.identity[0].oidc[0].issuer}:sub": "system:serviceaccount:production:user-service-sa"

}

}

}]

})

}

# Attach policy granting access to specific S3 bucket

resource "aws_iam_role_policy" "user_service_s3_policy" {

name = "user-service-s3-access"

role = aws_iam_role.user_service_role.id

policy = jsonencode({

Version = "2012-10-17"

Statement = [{

Effect = "Allow"

Action = [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject"

]

Resource = "arn:aws:s3:::user-uploads-prod/*"

}]

})

}

# Annotate Kubernetes service account with IAM role

resource "kubernetes_service_account" "user_service" {

metadata {

name = "user-service-sa"

namespace = "production"

annotations = {

"eks.amazonaws.com/role-arn" = aws_iam_role.user_service_role.arn

}

}

}

Similar patterns exist for GCP Workload Identity and Azure Managed Identity, but each is cloud-specific. We document them separately and train engineers on each cloud's IAM model.

Avoid custom identity abstraction layers. We evaluated building a unified IAM service that would abstract AWS IAM, GCP IAM, and Azure RBAC behind a single API. It would've taken six months to build and introduced a single point of failure for all cloud access. Instead, we accepted that each cloud has its own IAM system, documented the patterns, and moved on. Engineers learn each cloud's IAM—it's part of becoming proficient with that cloud.

Principle: Use federated identity (Okta) for human access, cloud-native service accounts for application access. Don't try to unify IAM across clouds—the complexity isn't worth it.

Infrastructure as Code Across Clouds

Terraform for Multi-Cloud

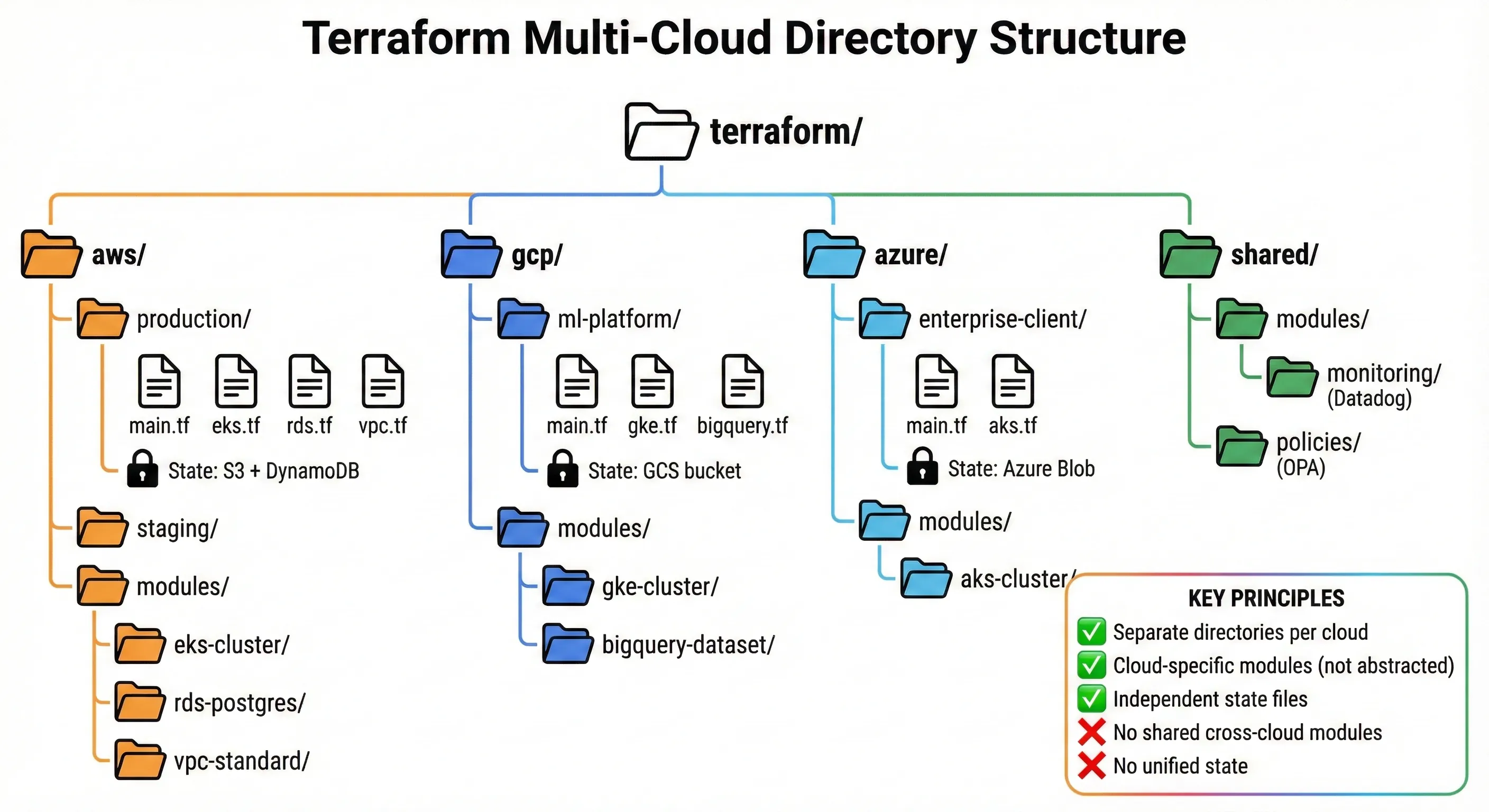

Terraform Multi-Cloud Directory Structure

Terraform is our primary IaC tool precisely because it supports multiple cloud providers without requiring us to build abstractions. We use Terraform with cloud-specific modules—not generic modules that work across all clouds. This keeps the benefits of Terraform (declarative configuration, state management, plan/apply workflow) without the downsides of over-abstraction.

Our Terraform project structure:

terraform/

├── aws/

│ ├── production/

│ │ ├── main.tf

│ │ ├── eks.tf

│ │ ├── rds.tf

│ │ ├── vpc.tf

│ │ └── variables.tf

│ ├── staging/

│ │ └── ...

│ └── modules/

│ ├── eks-cluster/

│ ├── rds-postgres/

│ └── vpc-standard/

├── gcp/

│ ├── ml-platform/

│ │ ├── main.tf

│ │ ├── gke.tf

│ │ ├── bigquery.tf

│ │ └── variables.tf

│ └── modules/

│ ├── gke-cluster/

│ └── bigquery-dataset/

├── azure/

│ ├── enterprise-client/

│ │ ├── main.tf

│ │ ├── aks.tf

│ │ └── variables.tf

│ └── modules/

│ └── aks-cluster/

└── shared/

├── modules/

│ └── monitoring/ (DataDog configuration)

└── policies/ (OPA policies)

Notice: Separate directories per cloud, not unified infrastructure. AWS production infrastructure is in aws/production/, GCP ML platform is in gcp/ml-platform/. They don't share modules because AWS modules and GCP modules do different things. An AWS EKS cluster module configures VPC networking, IAM roles for service accounts, and security groups—none of which exist in GCP. A GCP GKE cluster module configures Workload Identity, Google Cloud Armor, and network policies differently than AWS.

State management: We use separate Terraform state files for each cloud and each environment. AWS production state lives in an S3 bucket with DynamoDB state locking. GCP ML platform state lives in a GCS bucket. Azure state lives in Azure Blob Storage. We don't try to unify state across clouds. Each cloud's infrastructure is independent—if we lose AWS state, it doesn't affect GCP.

Here's our production AWS main configuration:

# aws/production/main.tf

terraform {

required_version = ">= 1.5.0"

required_providers {

aws = {

source = "hashicorp/aws"

version = "~> 5.0"

}

}

backend "s3" {

bucket = "company-terraform-state"

key = "aws/production/terraform.tfstate"

region = "us-east-1"

encrypt = true

dynamodb_table = "terraform-state-lock"

}

}

provider "aws" {

region = var.aws_region

default_tags {

tags = {

Environment = "production"

ManagedBy = "terraform"

CostCenter = "engineering"

}

}

}

# VPC configuration

module "vpc" {

source = "../modules/vpc-standard"

vpc_cidr = "10.0.0.0/16"

availability_zones = ["us-east-1a", "us-east-1b", "us-east-1c"]

environment = "production"

}

# EKS cluster

module "eks" {

source = "../modules/eks-cluster"

cluster_name = "production-cluster"

cluster_version = "1.28"

vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc_id

subnet_ids = module.vpc.private_subnet_ids

node_groups = {

general = {

desired_size = 6

min_size = 3

max_size = 12

instance_types = ["m5.xlarge"]

}

compute_optimized = {

desired_size = 3

min_size = 2

max_size = 10

instance_types = ["c5.2xlarge"]

}

}

}

# RDS Aurora PostgreSQL

module "database" {

source = "../modules/rds-postgres"

identifier = "production-db"

engine_version = "15.4"

instance_class = "db.r6g.2xlarge"

allocated_storage = 100

vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc_id

subnet_ids = module.vpc.database_subnet_ids

backup_retention_period = 30

enabled_cloudwatch_logs_exports = ["postgresql"]

# Aurora-specific configuration

aurora_cluster_mode = true

replica_count = 2

}

And our GCP ML platform configuration (completely separate):

# gcp/ml-platform/main.tf

terraform {

required_version = ">= 1.5.0"

required_providers {

google = {

source = "hashicorp/google"

version = "~> 5.0"

}

}

backend "gcs" {

bucket = "company-terraform-state-gcp"

prefix = "ml-platform/terraform.tfstate"

}

}

provider "google" {

project = var.gcp_project

region = var.gcp_region

}

# GKE cluster for ML inference

module "gke" {

source = "../modules/gke-cluster"

cluster_name = "ml-platform-cluster"

region = "us-central1"

node_pools = [{

name = "general-pool"

machine_type = "n2-standard-8"

min_count = 2

max_count = 20

disk_size_gb = 100

}, {

name = "gpu-pool"

machine_type = "n1-standard-8"

accelerator_type = "nvidia-tesla-t4"

accelerator_count = 1

min_count = 0

max_count = 10

}]

workload_identity_enabled = true

}

# BigQuery dataset for analytics

resource "google_bigquery_dataset" "analytics" {

dataset_id = "analytics_prod"

friendly_name = "Production Analytics"

location = "US"

default_table_expiration_ms = 31536000000 # 365 days

access {

role = "OWNER"

user_by_email = "ml-platform-sa@${var.gcp_project}.iam.gserviceaccount.com"

}

access {

role = "READER"

domain = "company.com"

}

}

# Cloud Storage for ML artifacts

resource "google_storage_bucket" "ml_artifacts" {

name = "${var.gcp_project}-ml-artifacts"

location = "US"

uniform_bucket_level_access = true

lifecycle_rule {

condition {

age = 90

}

action {

type = "SetStorageClass"

storage_class = "NEARLINE"

}

}

versioning {

enabled = true

}

}

Notice how different these configurations are—no shared modules, completely different resources, different state backends. This is intentional. AWS infrastructure and GCP infrastructure serve different purposes and should be managed independently.

Workspace strategy: We don't use Terraform workspaces for multi-cloud. Workspaces work well for environment separation within a single cloud (production/staging/dev on AWS), but they're confusing across clouds. Instead, we use separate directories. It's clearer, state management is simpler, and there's no risk of accidentally applying AWS changes to GCP.

Our Terraform workflow:

- Engineers make changes in feature branches

- CI runs

terraform planautomatically on pull request - Plan output is posted as PR comment for review

- After approval, engineer runs

terraform applyfrom their machine (we don't auto-apply to production) - State changes are committed to S3/GCS with versioning enabled

We run Terraform Cloud for our AWS infrastructure but use local state for GCP and Azure (smaller footprint, less critical). This is pragmatic—we pay for Terraform Cloud features where they add value (AWS is 60% of our infrastructure), but not everywhere.

The key insight: Use Terraform's multi-provider support, but don't try to make cloud-agnostic modules. Cloud-specific modules that use cloud-native features are simpler, more maintainable, and more powerful than abstracted modules that work everywhere but excel nowhere.

When NOT to Use Terraform

Terraform isn't always the right answer. I've pushed back on "Terraform everything" mandates because cloud-native tools sometimes fit better.

AWS CloudFormation has advantages for AWS-specific deployments. CloudFormation integrates deeply with AWS services—it understands service dependencies, handles rollback better for complex stacks, and supports some AWS features before Terraform providers catch up. We use CloudFormation for our AWS SAM (Serverless Application Model) deployments because SAM is built on CloudFormation and the integration is seamless. Fighting that by converting to Terraform would add complexity for no benefit.

Google Cloud Deployment Manager is simpler for small GCP projects. For our one-off GCP projects (prototypes, experiments), writing Deployment Manager templates in Python or YAML is faster than setting up Terraform with GCS backend. Once a project grows past 10 resources or becomes production-critical, we migrate to Terraform. But for quick experiments, Deployment Manager is fine.

Azure Resource Manager (ARM) templates or Bicep work better for some Azure scenarios, especially when using Azure-specific features like Azure Policy or Azure Blueprints. Our enterprise clients who are deep in the Azure ecosystem prefer Bicep—their teams know it, their compliance frameworks expect it. We use Terraform for our core Azure infrastructure but don't force it on client-managed resources.

Team expertise matters more than tool consistency. If your team knows CloudFormation deeply and Terraform superficially, using CloudFormation is probably faster and less error-prone. "Consistency" isn't valuable if it slows down delivery or increases errors. We have one team member who's a CloudFormation expert—we let them use CloudFormation for their projects rather than forcing Terraform for theological reasons.

When we choose Terraform: Multi-cloud projects, projects requiring complex state management, projects needing sophisticated dependency graphs, and anything that benefits from Terraform's mature ecosystem (providers, modules, tooling). When we don't: Simple single-cloud deployments, serverless applications tightly integrated with cloud-native frameworks, and projects owned by teams with strong cloud-native tool expertise.

The rule: Choose the right tool for the context. Terraform is often right, but not always. Don't optimize for consistency theater—optimize for team velocity and operational simplicity.

Policy as Code Across Clouds

One area where abstraction does make sense: security and compliance policies. We use Open Policy Agent (OPA) to enforce policies across all three clouds. OPA policies are cloud-agnostic—they evaluate JSON/YAML input against rules you define. This lets us enforce consistent security posture across AWS, Azure, and GCP without writing cloud-specific policy enforcement.

Here's a real OPA policy from our security team:

# Policy: All production databases must have encryption enabled

package database_encryption

deny[msg] {

# AWS RDS instance check

input.resource_type == "aws_db_instance"

input.environment == "production"

not input.storage_encrypted

msg = sprintf("Production RDS instance '%s' must have storage_encrypted=true", [input.resource_name])

}

deny[msg] {

# GCP Cloud SQL instance check

input.resource_type == "google_sql_database_instance"

input.environment == "production"

not input.settings[_].ip_configuration[_].require_ssl

msg = sprintf("Production Cloud SQL instance '%s' must require SSL connections", [input.resource_name])

}

deny[msg] {

# Azure SQL database check

input.resource_type == "azurerm_mssql_database"

input.environment == "production"

not input.transparent_data_encryption_enabled

msg = sprintf("Production Azure SQL database '%s' must have TDE enabled", [input.resource_name])

}

# Policy: Production workloads must have backup enabled

deny[msg] {

input.resource_type in ["aws_db_instance", "google_sql_database_instance", "azurerm_mssql_database"]

input.environment == "production"

backup_retention_days := object.get(input, "backup_retention_period", 0)

backup_retention_days < 7

msg = sprintf("Production database '%s' must have at least 7 days backup retention", [input.resource_name])

}

# Policy: Public access must be disabled for production databases

deny[msg] {

input.resource_type == "aws_db_instance"

input.environment == "production"

input.publicly_accessible == true

msg = sprintf("Production RDS instance '%s' cannot be publicly accessible", [input.resource_name])

}

deny[msg] {

input.resource_type == "google_sql_database_instance"

input.environment == "production"

input.settings[_].ip_configuration[_].ipv4_enabled == true

public_networks := [net | net := input.settings[_].ip_configuration[_].authorized_networks[_]; net.value == "0.0.0.0/0"]

count(public_networks) > 0

msg = sprintf("Production Cloud SQL instance '%s' cannot allow public internet access (0.0.0.0/0)", [input.resource_name])

}

We integrate OPA into our Terraform CI pipeline using Conftest. Every terraform plan gets evaluated against our OPA policies before apply is allowed:

# CI pipeline script

#!/bin/bash

# Run terraform plan and save output

terraform plan -out=tfplan.binary

terraform show -json tfplan.binary > tfplan.json

# Run OPA policy checks

conftest test tfplan.json --policy ./policies/ --namespace terraform

# If policies pass, allow apply

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

echo "✅ Policy checks passed"

# Proceed to apply (manual or automated)

else

echo "❌ Policy violations detected. Fix before applying."

exit 1

fi

This catches policy violations before they reach production. Last quarter, OPA policies blocked 23 attempted deployments that would have violated our security posture—databases without encryption, S3 buckets with public access, production instances without backups. The violations were caught in CI, not in production.

Why OPA works for multi-cloud: Security policies are genuinely similar across clouds. "Databases must be encrypted" is a universal requirement—the specific encryption mechanism differs (AWS KMS vs GCP Cloud KMS vs Azure Key Vault), but the policy intent is identical. OPA lets us write that policy once and enforce it everywhere. This is appropriate abstraction—we're abstracting the policy intent, not the infrastructure implementation.

We also use Sentinel (HashiCorp's policy framework) for some Terraform-specific policies, but OPA is more flexible for our multi-cloud needs. Sentinel integrates better with Terraform Cloud, but OPA works with any tool and any cloud.

Policy categories we enforce:

- Security: Encryption at rest, encryption in transit, no public access to databases, MFA required for console access, IAM role least privilege

- Compliance: Data residency rules, backup retention minimums, audit logging enabled, specific compliance frameworks (SOC2, PCI-DSS)

- Cost control: Maximum instance sizes in non-production, required auto-shutdown tags for dev resources, prohibition of certain expensive services in staging

- Operational standards: Required tags (Environment, Owner, CostCenter), naming conventions, mandatory health checks for production services

Policy as code gave us consistency without sacrificing cloud-specific capabilities. We enforce the same security posture across AWS, Azure, and GCP, but each cloud's resources use cloud-native features for implementation.

Observability Across Clouds

Unified Monitoring

Multi-Cloud: The Promise vs The Reality

Observability across multiple clouds is hard. You can use cloud-native tools (AWS CloudWatch, GCP Cloud Monitoring, Azure Monitor) and aggregate data centrally, or you can use a third-party unified platform. We chose the hybrid approach: Datadog for application-level observability, cloud-native tools for infrastructure metrics.

Why Datadog: After evaluating Datadog, New Relic, and Dynatrace, we chose Datadog for several reasons. First, their multi-cloud support is mature—native integrations for AWS, GCP, and Azure that collect metrics without custom instrumentation. Second, their APM (Application Performance Monitoring) provides distributed tracing across our microservices, regardless of which cloud they run on. Third, their pricing model was 30% cheaper than New Relic at our scale (200+ hosts, 500+ containers).[1]

Our Datadog setup collects:

- Application metrics: Request rates, error rates, latency percentiles (p50, p95, p99) for every service

- Infrastructure metrics: CPU, memory, disk, network for all VMs and containers

- Custom business metrics: User signups, payment transactions, ML model predictions

- Distributed traces: End-to-end request traces across microservices and clouds

- Logs: Application logs, access logs, security logs (we ship 2TB logs daily)

Cost: Datadog costs us $18,000 monthly for our full observability stack. This includes APM, infrastructure monitoring, log management, and synthetic monitoring. We evaluated building this ourselves with open-source tools (Prometheus, Grafana, Jaeger, ELK stack) and estimated $60,000 engineering time to build and $40,000 annually to operate. Datadog was cheaper.

Cloud-native for infrastructure: We still use CloudWatch, Cloud Monitoring, and Azure Monitor for infrastructure-level metrics and alerts. AWS CloudWatch alarms trigger Auto Scaling for our EKS node groups. GCP Cloud Monitoring alerts our on-call when GKE cluster health degrades. Azure Monitor tracks our enterprise client resource utilization for billing. These cloud-native tools are free (included in cloud costs) and deeply integrated with cloud services. We don't duplicate them in Datadog—we let each tool do what it does best.

Architecture: Datadog agents run as DaemonSets in our Kubernetes clusters (EKS, GKE, AKS). They collect metrics and logs from pods and ship to Datadog's SaaS platform. For non-Kubernetes workloads (RDS, Lambda, managed services), we use Datadog's cloud integrations that pull metrics via cloud APIs. For distributed tracing, we instrument our applications with OpenTelemetry and export traces to Datadog.

The value: Unified dashboard showing system health across all clouds. Our SRE team has one dashboard showing request rates from AWS services, ML inference latency from GCP services, and enterprise client health from Azure services. When something breaks, we see it immediately—regardless of which cloud it's on. This unified view is worth the $18K monthly cost.

Logging Strategy

Logs are the most expensive part of observability at scale. We generate 2TB of logs daily across all clouds. Shipping, storing, and indexing that volume requires careful cost optimization.

Our logging architecture:

-

Collection: Fluentd runs as DaemonSet in Kubernetes, collecting container logs. For managed services (RDS, Lambda, Cloud Functions), we use cloud-native log shipping (CloudWatch Logs → Kinesis Firehose → S3, Cloud Logging → Pub/Sub → Cloud Storage).

-

Routing: Hot logs (last 7 days, fully indexed, searchable) go to Datadog Logs. Warm logs (8-30 days, partially indexed) go to AWS S3 in structured format. Cold logs (31-365 days, archived) go to S3 Glacier.

-

Querying: Recent logs are searched in Datadog. Older logs are queried using AWS Athena against S3 (we convert logs to Parquet format for efficient querying).

Cost breakdown:

- Datadog Logs (7 days retention, fully indexed): $8,000/month

- AWS S3 Standard (warm logs, 23 days): $1,200/month

- AWS S3 Glacier (cold logs, 11 months): $400/month

- AWS Athena queries: $200/month average

- Total: $9,800/month

Before this optimization, we stored all logs in Datadog for 30 days, which cost $28,000 monthly. The new architecture saved $18,200 monthly ($218K annually) with minimal impact on log accessibility. We query cold logs maybe 10 times per month—usually for compliance audits or post-incident deep dives.

Here's our Fluentd configuration for multi-cloud log shipping:

# Fluentd DaemonSet configuration

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: fluentd-config

namespace: kube-system

data:

fluent.conf: |

# Input: Collect container logs

<source>

@type tail

path /var/log/containers/*.log

pos_file /var/log/fluentd-containers.log.pos

tag kubernetes.*

read_from_head true

<parse>

@type json

time_format %Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S.%NZ

</parse>

</source>

# Filter: Add Kubernetes metadata

<filter kubernetes.**>

@type kubernetes_metadata

@id filter_kube_metadata

</filter>

# Filter: Parse application logs

<filter kubernetes.var.log.containers.**>

@type parser

key_name log

reserve_data true

<parse>

@type json

</parse>

</filter>

# Output: Hot logs to Datadog (production only)

<match kubernetes.var.log.containers.**production**>

@type datadog

@id out_datadog

api_key "#{ENV['DATADOG_API_KEY']}"

dd_source kubernetes

include_tag_key true

<buffer>

@type memory

flush_interval 10s

</buffer>

</match>

# Output: Warm logs to S3 (all environments)

<match kubernetes.**>

@type s3

@id out_s3

s3_bucket company-logs-#{ENV['CLOUD_PROVIDER']}

s3_region us-east-1

path logs/%Y/%m/%d/

<buffer tag,time>

@type file

path /var/log/fluent/s3

timekey 3600 # 1 hour chunks

timekey_wait 10m

chunk_limit_size 256m

</buffer>

<format>

@type json

</format>

</match>

Log retention policy by compliance requirement:

- Production application logs: 365 days (SOC2 requirement)

- Security and audit logs: 7 years (PCI-DSS requirement)

- Non-production logs: 30 days (development convenience)

- Debug logs: 7 days (noise reduction)

Cross-cloud log correlation: Datadog's distributed tracing connects logs across clouds. When a request starts on AWS, calls a service on GCP, and returns to AWS, all logs are correlated by trace ID. This is critical for debugging—we can follow a user request across cloud boundaries and see the complete picture.

Distributed Tracing

Distributed tracing is essential for multi-cloud microservices. Without it, debugging failures across cloud boundaries is nearly impossible. We use OpenTelemetry for instrumentation and Datadog APM as the tracing backend.

Why OpenTelemetry: It's vendor-neutral. If we decide to switch from Datadog to Jaeger or Tempo later, we change the exporter configuration—not the instrumentation code. Our applications send traces to the OpenTelemetry Collector, which forwards to Datadog. This gives us flexibility without sacrificing Datadog's excellent UI and analysis tools.

Instrumentation example (Python service):

# app.py - FastAPI service with OpenTelemetry tracing

from fastapi import FastAPI

from opentelemetry import trace

from opentelemetry.exporter.otlp.proto.grpc.trace_exporter import OTLPSpanExporter

from opentelemetry.sdk.trace import TracerProvider

from opentelemetry.sdk.trace.export import BatchSpanProcessor

from opentelemetry.instrumentation.fastapi import FastAPIInstrumentor

from opentelemetry.instrumentation.requests import RequestsInstrumentor

from opentelemetry.instrumentation.sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemyInstrumentor

# Initialize tracing

trace.set_tracer_provider(TracerProvider())

otlp_exporter = OTLPSpanExporter(

endpoint="http://otel-collector:4317",

insecure=True

)

trace.get_tracer_provider().add_span_processor(

BatchSpanProcessor(otlp_exporter)

)

# Create FastAPI app

app = FastAPI()

# Auto-instrument frameworks

FastAPIInstrumentor.instrument_app(app)

RequestsInstrumentor().instrument()

SQLAlchemyInstrumentor().instrument()

# Application code - tracing happens automatically

@app.get("/users/{user_id}")

async def get_user(user_id: int):

# This request is automatically traced

# Including database queries, external API calls, etc.

user = db.query(User).filter(User.id == user_id).first()

# Make cross-cloud API call (automatically traced)

recommendations = requests.get(

f"https://ml-api.gcp.company.com/recommendations/{user_id}"

)

return {

"user": user,

"recommendations": recommendations.json()

}

Trace propagation across clouds: OpenTelemetry automatically propagates trace context via HTTP headers. When our AWS service calls our GCP service, the trace ID and span ID are sent in the traceparent header. The GCP service continues the trace, so we see the complete request path in Datadog.

Real-world example: Last month, we debugged a P95 latency spike (350ms → 2.1 seconds) affecting user login. The distributed trace showed:

- Request starts at AWS API Gateway (10ms)

- Auth service on AWS EKS validates token (45ms)

- Auth service calls user-profile service on GCP GKE (1,800ms ← problem!)

- Response returns to client (2.1s total)

The trace revealed the issue: Our GCP service was making an uncached database query for each request. We added Redis caching, and P95 latency dropped to 120ms. Without distributed tracing across clouds, this would've taken days to debug. With tracing, it took 20 minutes.

Sampling strategy: We sample 100% of error traces, 100% of traces >1 second, and 10% of successful fast traces. This keeps tracing costs manageable ($4,000/month) while ensuring we capture all problematic requests. At full 100% sampling, cost would be $40,000 monthly—unjustified for our needs.

Cost Management

Multi-Cloud FinOps

Managing costs across three clouds is complex. Each cloud has different pricing models, discount programs, and billing structures. We use CloudHealth by VMware (recently migrated from CloudCheckr) for unified cost visibility.

What CloudHealth gives us:

- Single dashboard for all cloud spend: AWS ($110K/month), GCP ($46K/month), Azure ($44K/month), total $200K/month

- Cost allocation by team/project: Engineering $120K, Data Science $50K, Enterprise Clients $30K

- Anomaly detection: Alerts when daily spend exceeds baseline by >20%

- Rightsizing recommendations: Identifies oversized instances, unused resources

- Reserved Instance/Savings Plan optimization: Models different commitment scenarios

CloudHealth costs $3,000/month (1.5% of our cloud spend). It pays for itself by catching waste. Last quarter, CloudHealth identified:

- $8,000/month in orphaned EBS volumes (AWS)

- $3,500/month in oversized Cloud SQL instances (GCP)

- $4,200/month in non-production resources running 24/7 unnecessarily

We implemented auto-shutdown for dev/staging environments (automatically stop resources outside business hours), which saved an additional $12,000 monthly.

Comparing costs across clouds (apples to oranges problem): Cloud pricing is deliberately complex and hard to compare. AWS, GCP, and Azure price identical workloads differently. Here's a real comparison for equivalent compute:

| Workload | AWS | GCP | Azure | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 vCPU, 32GB RAM VM (on-demand) | $0.384/hour (m5.2xlarge) | $0.379/hour (n2-standard-8) | $0.416/hour (Standard_D8s_v3) | GCP (-1.3%) |

| Same with 1-year commit | $0.231/hour (RI) | $0.263/hour (CUD) | $0.270/hour (RI) | AWS (-12%) |

| Same with 3-year commit | $0.139/hour (RI) | $0.184/hour (CUD) | $0.170/hour (RI) | AWS (-24%) |

| 100TB object storage/month | $2,300 (S3 Standard) | $2,000 (Cloud Storage Standard) | $2,150 (Blob Hot) | GCP (-13%) |

| Data transfer out (1TB) | $90 | $120 | $87 | Azure (-3%) |

| Managed PostgreSQL (4 vCPU, 16GB) | $290/month (RDS) | $268/month (Cloud SQL) | $310/month (Azure SQL) | GCP (-8%) |

Notice: GCP wins on on-demand and storage, AWS wins on committed discounts, Azure is generally most expensive. But these comparisons are incomplete—they don't account for data transfer costs, required supporting services, or operational complexity of managing resources across clouds.

Our cost optimization strategies:

-

Commitment-based discounts: We committed to $60K/month AWS spend for 3 years (Savings Plans), saving 40% vs on-demand. GCP committed use discounts save us 25% on persistent workloads. Azure Reserved Instances save 30% for enterprise client workloads.

-

Spot/Preemptible instances: ML training jobs run on GCP preemptible instances (60% cheaper than on-demand). Batch processing uses AWS Spot instances (70% cheaper). We save $25,000 monthly on interruptible workloads.

-

Rightsizing: We run automated analysis monthly to identify oversized instances. Last analysis found 23 instances where we were paying for 8 vCPUs but using <20% CPU. We downsized them, saving $6,000/month.

-

Storage lifecycle policies: S3 objects transition to Infrequent Access after 30 days, Glacier after 90 days. This saves $15,000/month on 200TB of historical data we rarely access.

-

Reserved capacity: We buy RDS Reserved Instances, ElastiCache Reserved Nodes, and Elasticsearch Reserved Instances for known long-term usage. This saves 30-40% vs on-demand.

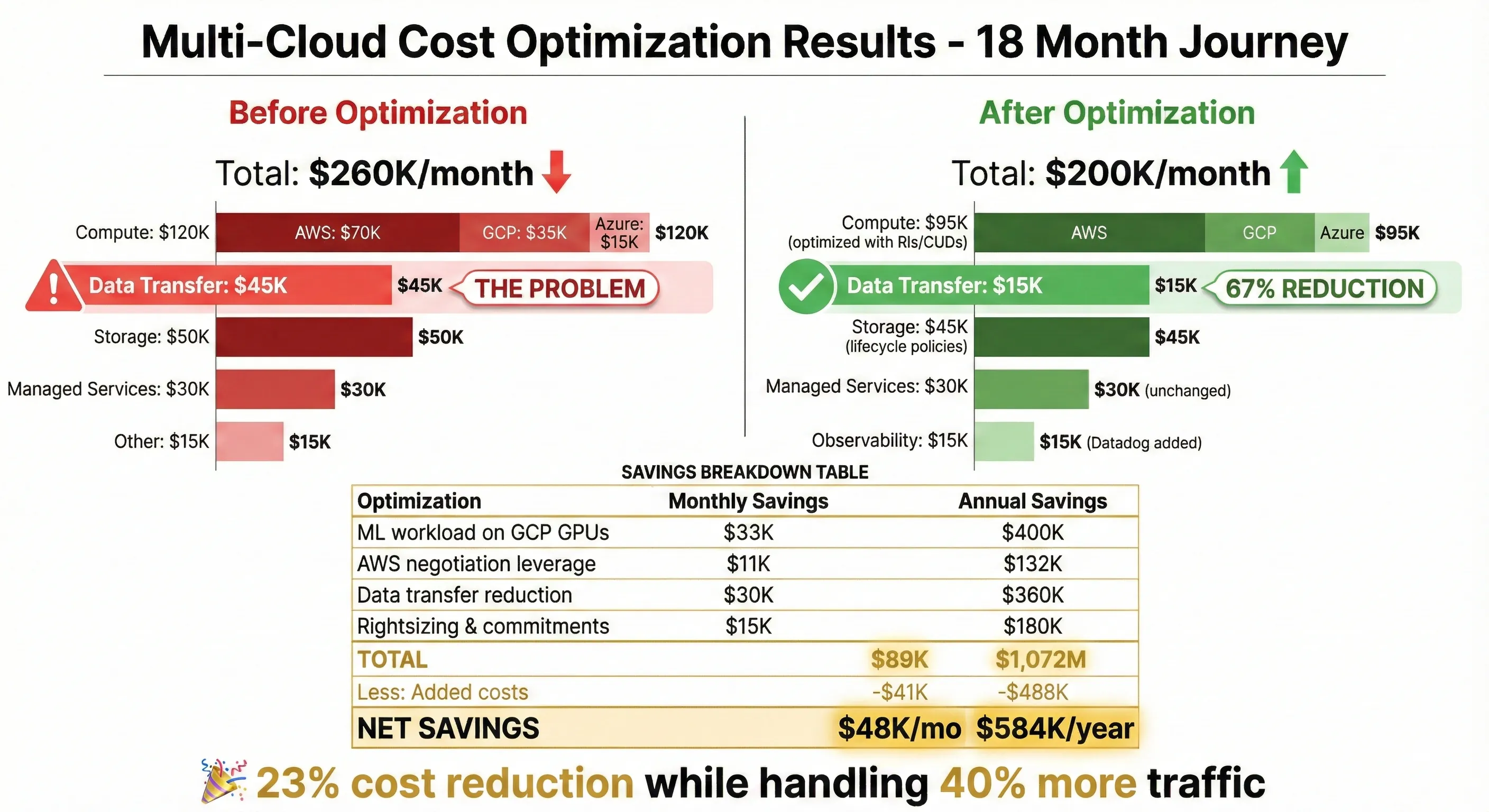

Total cost optimization achieved: Through disciplined FinOps practices, we reduced our cloud spend from $260K/month to $200K/month over 18 months—23% reduction ($720K annually) while handling 40% more traffic. The biggest wins came from commitment-based discounts ($35K/month) and eliminating waste ($15K/month).

Data Transfer Costs

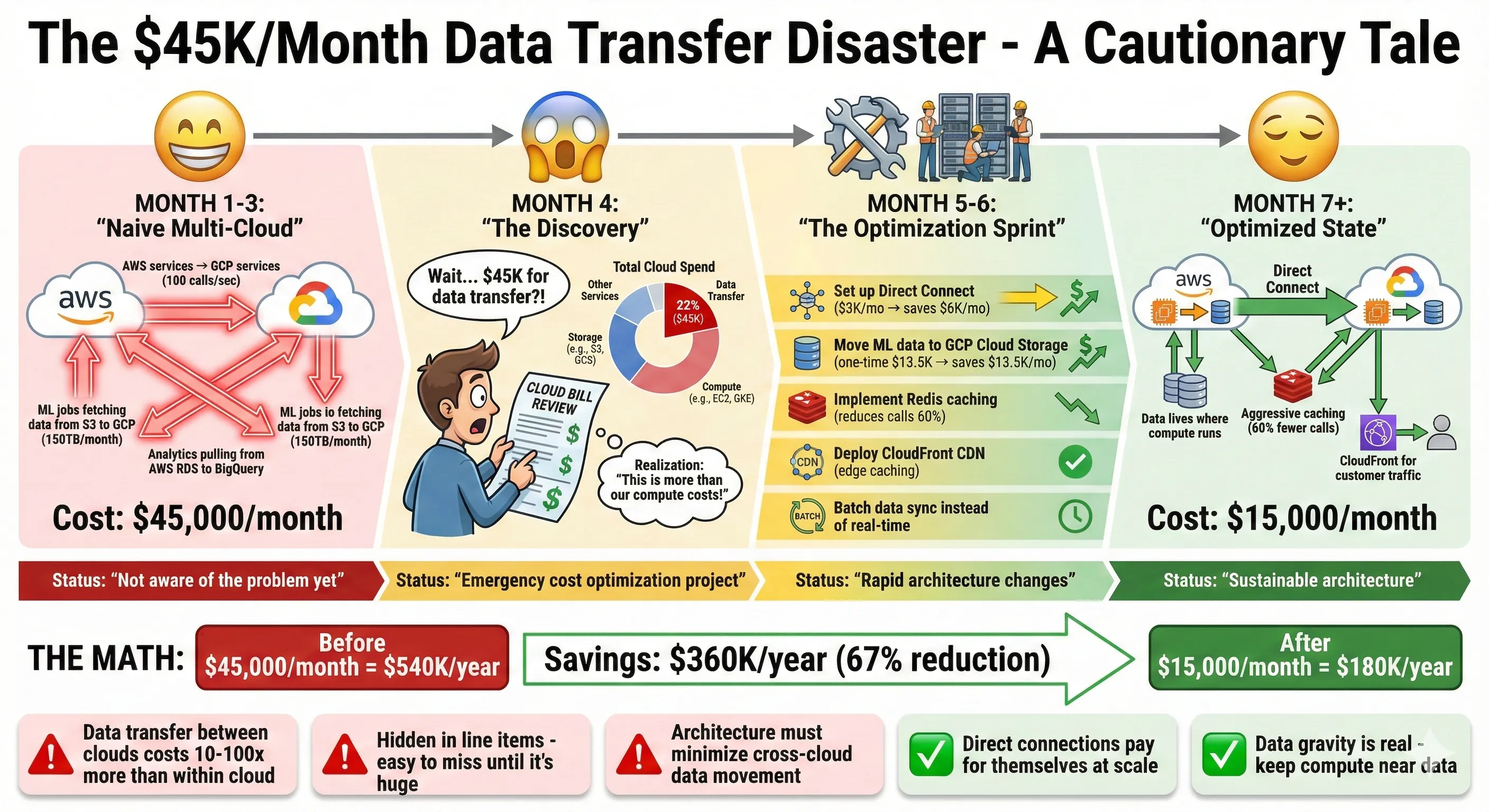

The $45K/Month Data Transfer Disaster - A Cautionary Tale

Data transfer is the hidden killer in multi-cloud architecture. I mentioned this earlier, but it deserves its own focus because it's where most multi-cloud strategies fail financially.

Our $45K/month data transfer disaster: In our first six months of multi-cloud operation, we were bleeding $45,000 monthly on cross-cloud data transfer. We were naively treating clouds like regions within a single cloud—services on AWS freely called services on GCP, ML jobs on GCP fetched training data from S3, analytics queries in BigQuery pulled reference data from AWS RDS. Every GB transferred cost $0.09-$0.12.[2][3]

Here's what we were paying:

- AWS → GCP (ML training data): 150TB/month × $0.09 = $13,500

- GCP → AWS (ML inference results): 50TB/month × $0.12 = $6,000